When a pharmaceutical company spends over a decade and more than $2 billion to develop a new drug, it doesn’t just need a patent-it needs enough time to make that investment worthwhile. But here’s the problem: the clock on a patent starts ticking the day you file it, not the day you get FDA approval. By the time a drug finally hits the market, 5, 7, or even 10 years of its 20-year patent life may already be gone. That’s where Patent Term Restoration (PTE) comes in. It’s not a loophole. It’s a legal reset button designed to give drug makers back some of the time they lost waiting for regulators to approve their product.

How PTE Works: The Hatch-Waxman Act and the Regulatory Clock

Patent Term Restoration was created by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Named after its sponsors, Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, the law was meant to balance two competing goals: letting generic drugs enter the market faster while still rewarding innovators for their R&D. The core idea? If your patent expires while your drug is still stuck in FDA review, the government will give you back some of that lost time.

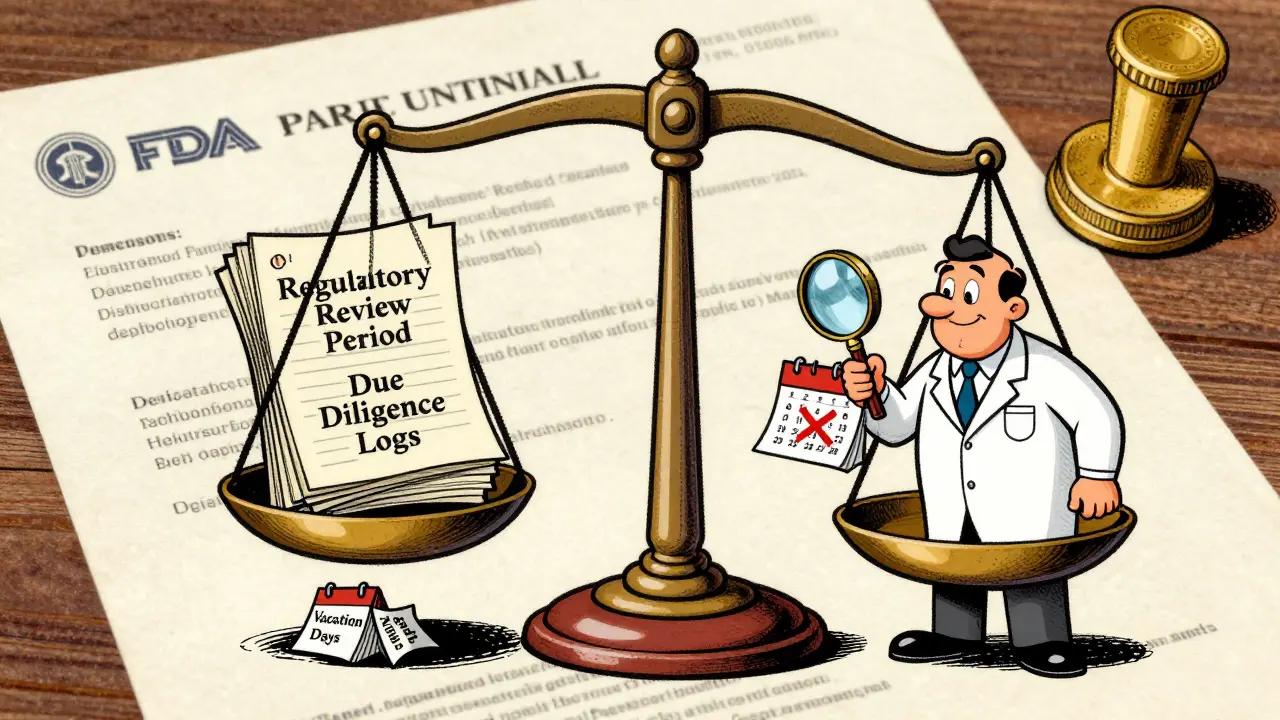

The math behind PTE isn’t simple, but the logic is. The formula looks like this: PTE = RRP - PGRRP - DD - ½(TP-PGTP). In plain terms, it takes the total time your drug spent under FDA review (Regulatory Review Period), subtracts the time before you even filed your patent (Pre-Grant Regulatory Review Period), then deducts any days where you weren’t actively pushing the application forward (Days of applicant’s due diligence). Half of the remaining time between your patent’s total life and its pre-grant life gets added back. The result? A maximum extension of five years.

But there’s a hard cap: even if you get the full five years, your patent can’t last more than 14 years after FDA approval. That means if your drug gets approved in 2030, the latest your patent can expire is 2044-even if the original patent term would have lasted longer. This keeps the system from becoming a permanent monopoly.

Who Qualifies? It’s Not Just for Pills

You might think PTE only applies to pills, but it covers more. The law includes human drugs, medical devices, food additives, color additives, and animal drugs. That last one matters-animal medications, like vaccines for livestock or treatments for pets, also get PTE. In 1988, Congress expanded the law to include animal drugs through the Generic Animal Drug and Patent Term Restoration Act. So if a company spends years getting approval for a new flea treatment for cats, they can still apply for PTE.

There’s one big catch: only one patent per product can get extended. That means if a company files multiple patents covering different aspects of the same drug-say, the active ingredient, the pill coating, and the dosing schedule-only one of them qualifies. And it has to be the patent that claims the product actually approved by the FDA. This stops companies from stacking extensions like a pyramid of exclusivity.

The Application Window: 60 Days and No Mercy

Timing is everything. The application for PTE must be filed within 60 days of the FDA’s official approval date. Miss that window? You lose the chance forever. No exceptions. No extensions. That’s why pharmaceutical companies have entire teams dedicated to tracking FDA decisions. One delay in paperwork, one missed deadline, and millions in potential revenue vanish.

But there’s a safety net: the Interim Extension. If your patent is set to expire in less than six months and the FDA hasn’t approved your drug yet, you can apply for a temporary extension. This keeps your patent alive while the final decision is pending. It’s not common, but for drugs on the edge of approval, it’s a lifeline.

Proof Matters: The Due Diligence Trap

The biggest reason PTE applications get denied? Incomplete documentation. The FDA doesn’t just want a list of dates. They want day-by-day proof that you were actively pushing the application forward. That means emails, meeting notes, lab reports, submission receipts, and correspondence with regulators-all of it. If you skipped a week because your team was on vacation, or if your regulatory team didn’t respond to an FDA request within 30 days, that’s a red flag.

According to the USPTO’s 2022 report, 12.7% of PTE applications were denied, mostly because applicants couldn’t prove continuous due diligence. One senior patent attorney on Reddit shared that their company once lost an extension because they failed to document a single 17-day gap between regulatory submissions. “It’s not about being perfect,” they wrote. “It’s about showing you tried.”

The FDA’s 2024 guidance on due diligence clarified what counts: every interaction with regulators must be recorded. Even a phone call. Even a text message. If you can’t prove you were moving the ball forward, you won’t get your time back.

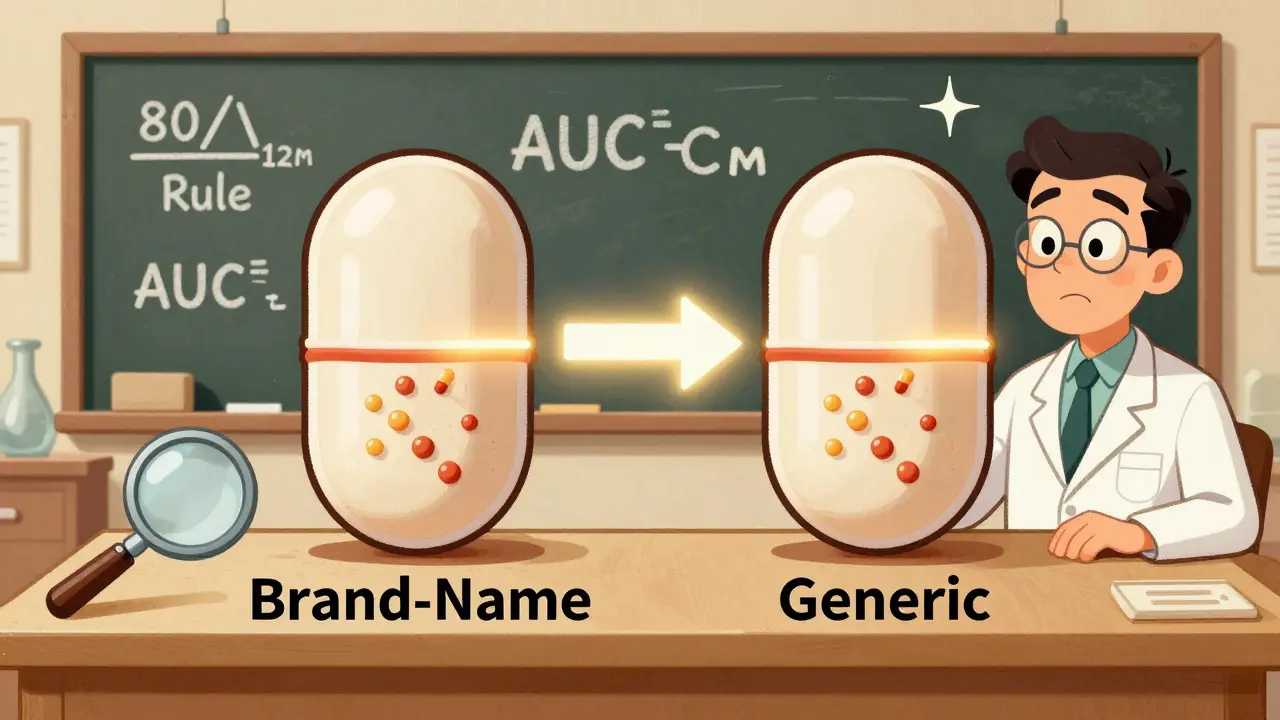

PTE vs. PTA: Don’t Confuse Them

People often mix up Patent Term Restoration (PTE) and Patent Term Adjustment (PTA). They sound similar, but they’re totally different. PTA is handled by the USPTO and fixes delays caused by the patent office itself-like if they took 3 years to examine your application instead of the legal 30 months. PTE, on the other hand, is all about FDA delays. The USPTO doesn’t even decide PTE eligibility. The FDA does. The USPTO just takes the FDA’s numbers and applies them.

Think of it this way: PTA is a bureaucratic correction. PTE is a compensation for regulatory wait times. One fixes government slowness. The other fixes the cost of being safe.

The Bigger Picture: Market Impact and Controversy

PTE isn’t just paperwork-it’s big business. Between 2010 and 2020, over 1,200 patent extensions were granted. In 2023 alone, the FDA processed 287 applications. Biologics, like monoclonal antibodies and gene therapies, now make up 34% of all PTE requests, up from 19% in 2018. That’s because these drugs take even longer to develop and approve.

But here’s the tension: while PTE was meant to restore lost time, it’s often used to extend monopolies far beyond what Congress intended. A 2022 Yale Law study found that 91% of drugs that got PTE kept their market dominance for years after the extension ended, thanks to secondary patents, evergreening tactics, and litigation. The FTC reported that drugs with PTE held onto 92% of their market share during the extension period. Once generics arrive, that drops to 37%.

And then there’s the cost. The Congressional Budget Office estimated PTE adds $4.2 billion a year to U.S. drug spending. Critics argue that the system has been gamed-78% of PTE applications now involve secondary patents, not the original compound. That’s not restoring time. That’s stretching it.

What’s Next? Digital Shifts and Possible Reforms

The FDA is working on modernizing the process. By Q2 2026, they plan to roll out a digital submission platform to replace paper forms and scattered emails. That should cut processing time, which averages 217 days now. The USPTO also saw a 7.3% jump in PTE applications in 2023, signaling more companies are using the tool.

But pressure is building. The proposed Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act would limit how PTE can be used, especially for biologics and follow-on drugs. The Government Accountability Office is set to release a full review of the program in December 2025. If they find PTE is doing more harm than good, Congress may change the rules.

For now, PTE remains a powerful tool for companies that know how to use it. It’s not a gift. It’s a negotiated trade: you get extra time, but only if you can prove you did everything right.

Can a patent be extended more than once for the same drug?

No. Only one patent per drug product can receive a term extension under PTE. Even if a company holds multiple patents covering different aspects of the same drug-like its chemical structure, delivery method, or formulation-only the patent that claims the FDA-approved product qualifies. This prevents companies from stacking extensions to delay generics indefinitely.

What happens if I miss the 60-day deadline to apply for PTE?

You lose the right to apply permanently. The 60-day window after FDA approval is strict. There are no exceptions, extensions, or appeals. Missing this deadline means the patent expires on its original date, and generics can enter the market immediately. That’s why pharmaceutical companies assign dedicated teams to monitor FDA decisions and file applications the moment approval is granted.

Does PTE apply to medical devices?

Yes. The Hatch-Waxman Act includes medical devices, along with human drugs, animal drugs, food additives, and color additives. Any product that requires FDA approval before commercial sale can qualify for PTE if the regulatory review period caused significant loss of patent life. This is especially important for complex devices that take years to get approved, such as implantable pacemakers or AI-driven diagnostic tools.

Can generic companies challenge a PTE grant?

Yes. Generic manufacturers can challenge the validity of a PTE grant through legal proceedings, often by arguing the patent doesn’t claim the approved product or that due diligence wasn’t proven. In 2024, the Federal Circuit case Eli Lilly v. USPTO set stricter standards for proving continuous progress during regulatory review, making it harder to obtain extensions. These challenges are common and can delay generic entry by years.

How long does the PTE application process take?

The FDA takes an average of 217 days to process a PTE application, based on its 2023 annual report. After the FDA provides its determination, the USPTO reviews and issues the extension. The entire process can take over a year. Companies often file early and request suspension of the application under 37 C.F.R. § 1.103 to align it with pending litigation or reissue patents, which can add more time.

Is PTE available outside the United States?

No. PTE is a U.S.-specific mechanism created by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Other countries have different systems. The European Union offers Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), which serve a similar purpose but have different rules and durations. Japan and Canada also have their own patent extension systems, but none are identical to the U.S. PTE program. If a company wants global protection, it must navigate each country’s unique rules.

Angie Datuin

February 10, 2026 AT 10:05Just read through this and honestly, it’s wild how much goes into getting one drug approved. I had no idea the patent clock starts ticking before the drug even hits the market. Makes you realize how much of a gamble this is for companies-and how fragile the timeline is.

Alex Ogle

February 10, 2026 AT 13:19Been in biotech for 12 years. The PTE system? It’s a lifeline. But also a minefield. I’ve seen teams lose millions because someone forgot to log a 3-day delay in submitting a protocol amendment. The FDA doesn’t care if you were on vacation. They care if the paperwork was late. It’s brutal, but fair.

Frank Baumann

February 11, 2026 AT 19:48OH MY GOD. I JUST REALIZED-this whole system is basically a legal loophole dressed up like a public service. They call it 'restoring time' but what it really is? A 5-year monopoly extension disguised as justice. And don’t even get me started on biologics. Those things take 15 years to develop and now they get 5 extra years of exclusivity? That’s not innovation. That’s rent-seeking. And we’re all paying for it in higher premiums. I swear, if you think drug companies are saints, you’ve never read a single SEC filing.

And the due diligence trap? That’s not a bug, it’s a feature. They want you to sweat. They want you to sweat so hard you document every damn text message. Because if you don’t, you lose. And when you lose? Generics come in. And suddenly, that $2,000 pill becomes $30. So yeah. The system works. For them.

And the 60-day window? That’s not a deadline. That’s a trapdoor. One missed email. One delayed PDF. One intern who didn’t check the FDA portal. And poof. $800 million in revenue gone. No appeals. No mercy. Just silence. And then the stock drops. And the investors scream. And the CEO blames compliance. But really? It’s just the system being designed to punish the careless. And we wonder why Big Pharma hires 50 people just to manage paperwork.

Scott Conner

February 13, 2026 AT 15:25Tatiana Barbosa

February 14, 2026 AT 09:49Y’all need to understand-PTE isn’t just about profit. It’s about survival. Think about the kids with rare diseases waiting for a drug that took 14 years to get approved. If we take away PTE, we take away the incentive to even try. Who’s gonna spend $2 billion on a drug that’ll be generic in 3 years? Not me. Not my company. Not anyone with half a brain. This isn’t greed. It’s necessity. And yes, some companies abuse it. But the system? It’s saving lives. Every day.

Also-medical devices? YES. A pacemaker with an AI algorithm? Took 9 years to get approved. Without PTE? That innovation dies on the vine. You want cheaper drugs? Fine. But don’t kill the pipeline that makes them possible.

John McDonald

February 14, 2026 AT 15:18Big Pharma hates this, but I’m gonna say it: PTE is the only reason we have new cancer drugs. I’ve seen patients on trial meds that would’ve never made it to market without this. Yeah, the extensions get abused. But the alternative? No innovation. Zero. Zip. Nada. I’d rather pay $10K for a life-saving drug than $0 for a dead patient.

Also-animal drugs. Don’t forget the pets. My dog got a new PTE-approved treatment last year. Cost $1,200. Worth every penny. So yeah. PTE matters. Even if you don’t have a human in the equation.

Andy Cortez

February 15, 2026 AT 09:00Camille Hall

February 15, 2026 AT 23:32One thing people miss: PTE isn’t just for big pharma. It’s for the small biotechs too-the ones with 12 people and a lab in a garage. Without this, they’d never survive long enough to get approval. The FDA process is a marathon. If you don’t get your time back, you’re dead before you even start. And yeah, some companies game it. But the system? It’s the only thing keeping the whole ecosystem alive.

Also-78% of extensions are on secondary patents? That’s a problem. But fixing it doesn’t mean killing PTE. It means tightening the rules. Maybe require the primary patent to be the one extended. Or cap total exclusivity at 12 years post-approval. We can fix it. We just have to stop screaming and start negotiating.

Joshua Smith

February 17, 2026 AT 17:43Had a friend work on a PTE application last year. The paperwork was insane. They had to submit every single email, every call log, even the Slack messages where they asked the FDA about a form. One time, the FDA asked for a clarification. They replied in 28 hours. The FDA said it took 30. They lost 2 days. That’s it. Two days. And that’s why the extension got cut by 11 months. It’s not about fairness. It’s about documentation. And if you’re not obsessive about it? You lose.

Also-did you know the USPTO doesn’t even review PTE? The FDA does. The USPTO just stamps it. So if the FDA says ‘yes,’ the USPTO says ‘ok.’ No second opinions. No appeals. Just paperwork. And if you mess it up? You’re out.

Ken Cooper

February 17, 2026 AT 21:58Wait wait wait-so if a company files 3 patents on the same drug, only ONE gets extended? And it has to be the one that matches the FDA-approved version? So if they accidentally patented the wrong formulation? Too bad? That’s wild. I feel like this is the kind of loophole that gets exploited. Like, ‘oh we’ll just file 10 patents and hope one sticks.’ But nope. Only one. And it’s gotta be exact. That’s… oddly fair? Kinda? I’m confused.

Also-what’s the deal with the ‘interim extension’? That’s like a temporary stay of execution. I love that. Like, ‘your patent is about to die, so we’ll let it live for 6 more months while you wait for the FDA to make up its mind.’ That’s actually kind of human. I didn’t expect that.

Patrick Jarillon

February 19, 2026 AT 05:35Here’s the truth they don’t tell you: PTE isn’t about restoring time. It’s about control. The FDA and the USPTO are in bed with Big Pharma. This whole system was designed by lobbyists to keep generics out. You think they care about innovation? Nah. They care about market share. Look at the stats-92% market share during PTE? That’s not innovation. That’s a cartel. And the fact that they’re now pushing digital submissions? That’s just to make it harder for small players to compete. They want everything centralized. Everything monitored. Everything locked down. This isn’t progress. It’s consolidation.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘due diligence’ trap. You think they want you to document every text? No. They want you to fail. Because when you fail? The patent expires. And then they sue you for infringement anyway. It’s all a game. And you’re not playing. You’re being played.

Andrew Jackson

February 20, 2026 AT 18:39This entire system is a disgrace to American innovation. The Founding Fathers envisioned patents as a limited monopoly to incentivize progress-not as a permanent revenue stream for corporate oligarchs. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a noble compromise. But today? It’s been perverted into a tool of economic warfare. We are subsidizing billion-dollar corporations with taxpayer-funded exclusivity, while ordinary citizens are priced out of life-saving medicine. This is not capitalism. This is feudalism with a corporate logo. And if Congress does not act to cap PTE at three years post-approval, we are complicit in the systematic erosion of public health. I say: abolish PTE. Let the market decide. Let innovation rise or fall on its own merits. Not on the back of a bureaucratic loophole.

Jacob den Hollander

February 22, 2026 AT 07:29As someone who grew up in the Netherlands, I’ve seen how SPCs work in the EU. They’re similar, but way more transparent. The extension is capped, public records are open, and generic manufacturers can challenge early. Here? It’s a black box. You file. You wait. You hope. And if you lose? No one tells you why. The FDA doesn’t publish denial reasons. The USPTO doesn’t explain. It’s all buried in PDFs no one reads. That’s not just inefficient-it’s unjust. We need transparency. We need data. We need to know who’s getting extensions, why, and how much it costs society. Right now? We’re flying blind.

Also-animal drugs. That’s beautiful. My cat’s on a PTE-approved medication. It’s not just about humans. It’s about all living things. And if we protect that? We protect something deeper than profit. We protect care.

Random Guy

February 23, 2026 AT 12:24so let me get this straight… we spend 10 years and $2B to make a pill, then we get 5 more years to sell it… but we can’t extend it more than once… and if we miss a text message… we lose it all…

man. this is the plot of a dark comedy. ‘The Patent’ starring a guy in a lab coat crying over a Slack notification.

Alex Ogle

February 24, 2026 AT 10:55Replying to the guy who said PTE is just corporate greed: you’re missing the point. The reason we have new drugs isn’t because Big Pharma is generous. It’s because they had a shot at recouping their investment. Without PTE, the next breakthrough for Alzheimer’s? It dies in Phase II. Because no investor would fund it. The math doesn’t work. PTE isn’t perfect. But it’s the only thing keeping the pipeline alive. And if you want cheaper drugs? Fix the system. Don’t kill it.