When you pick up a generic drug at the pharmacy, you might assume it’s just a cheaper version of the brand-name medicine. But behind that simple assumption is a rigorous scientific process the FDA demands before any generic drug hits the shelf. Bioequivalence studies are not optional-they’re the legal foundation that ensures a generic drug works exactly like its brand-name counterpart. Without these studies, the FDA wouldn’t approve a single generic product. And yet, many people don’t know what these studies actually measure, or why they matter.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

The FDA defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in how quickly and how much of the active drug enters your bloodstream compared to the original brand-name drug. It’s not about whether the pills look the same or have the same color. It’s about whether your body absorbs and uses the drug in the same way. This matters because even small differences in absorption can affect how well a drug works-or whether it causes side effects.For example, if a generic version of a blood thinner like warfarin is absorbed too slowly, it might not prevent clots. If it’s absorbed too fast, it could cause dangerous bleeding. The FDA doesn’t take chances. Every generic drug must prove it delivers the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate as the original. That’s the core of bioequivalence.

The Two Rules: Pharmaceutical and Bioequivalence

Before a generic drug can even start bioequivalence testing, it must first meet pharmaceutical equivalence. That means it has to contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, in the same dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection, etc.), and the same route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the brand-name drug. If it doesn’t match on these basics, the FDA won’t even consider it.Once pharmaceutical equivalence is confirmed, the real test begins: bioequivalence. This is where pharmacokinetic studies come in. These are clinical trials-usually done in 24 to 36 healthy adult volunteers-that track how the drug moves through the body. Researchers measure two key values: the area under the curve (AUC), which shows total drug exposure over time, and the maximum concentration in the blood (Cmax), which shows how fast the drug peaks.

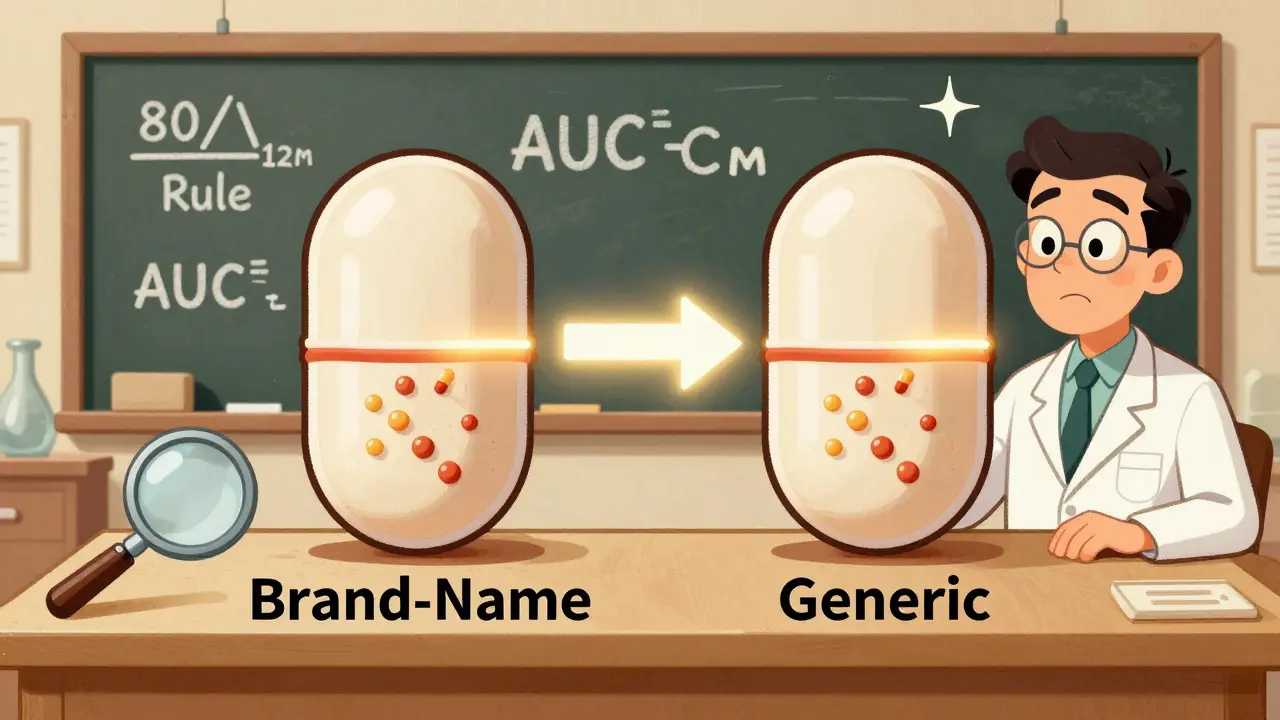

The 80/125 Rule: The Golden Standard

The FDA’s acceptance criteria are strict and based on decades of science. For a generic drug to be approved, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the test (generic) to reference (brand) drug must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC and Cmax. This is known as the 80/125 rule. It means the generic’s drug levels can’t be more than 20% lower or 25% higher than the brand’s. This range isn’t arbitrary-it’s based on real-world data showing that within this range, therapeutic outcomes are virtually identical.This rule applies to most systemic drugs taken by mouth. But it’s not one-size-fits-all. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or digoxin-the FDA tightens the range to 90-111%. These are drugs where even a small difference in blood levels can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure. The FDA knows this, and it adjusts the rules accordingly.

When In Vivo Studies Aren’t Needed

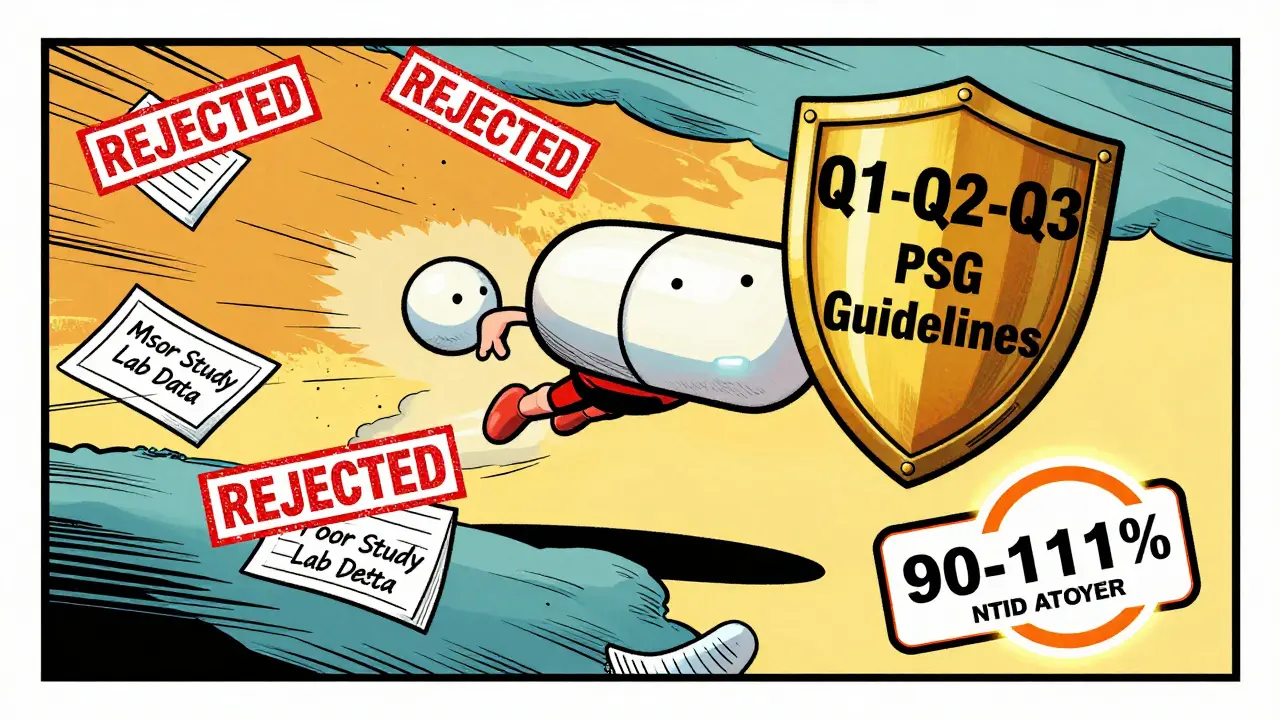

Not every generic drug needs a full clinical trial. The FDA allows biowaivers for certain products where absorption isn’t a concern. For example, if a generic is an eye drop or ear drop with the exact same ingredients and concentration as the original, the FDA may skip human testing. The same goes for topical creams meant to treat skin conditions locally, not systemically. In these cases, manufacturers can use in vitro tests-like measuring how fast the drug releases from the cream or how it moves through a synthetic skin membrane-to prove equivalence.The Q1-Q2-Q3 framework guides these decisions: Q1 means identical active and inactive ingredients; Q2 means the same dosage form and strength; Q3 means matching pH and physical properties. If all three are met, the FDA considers the product bioequivalent without human trials. This saves manufacturers time and money-and gets cheaper drugs to market faster.

Complex Drugs and New Science

Some drugs are harder to copy. Inhalers, injectable suspensions, topical ointments with complex bases, and drug-device combinations (like inhalers with built-in dose counters) don’t always behave predictably. For these, the FDA has started using advanced tools like physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. These computer simulations predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, rather than relying solely on human trials.The FDA also introduced scaled average bioequivalence (SABE) for highly variable drugs-those where the body absorbs them very differently from person to person. Instead of using the same 80/125 rule, the FDA adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the original drug is. This prevents good generics from being rejected just because the brand-name drug itself behaves inconsistently.

Why So Many Submissions Get Rejected

Despite clear guidelines, nearly 60% of generic drug applications get rejected on the first try. The most common reasons? Poor study design, small sample sizes, inaccurate lab measurements, or incomplete documentation. Many companies underestimate how precise the FDA expects the data to be. A single missing detail in the protocol-like how blood samples were stored or how the lab calibrated its instruments-can trigger a complete response letter, delaying approval by months.Companies that follow the FDA’s product-specific guidances (PSGs) have a much better chance. As of late 2023, there were over 2,100 PSGs available, each tailored to a specific drug. Following one can increase first-cycle approval rates from 29% to 68%. That’s not luck-it’s preparation.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Access, and Safety

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but cost only 23% of total drug spending. That’s because bioequivalence studies, while expensive, prevent the need for long-term clinical trials. Without them, manufacturers would have to prove safety and effectiveness from scratch-something brand-name companies do at a cost of over $2 billion per drug. The FDA’s system strikes a balance: it protects patients while keeping generics affordable.The FDA’s recent Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program helps too. It speeds up review for generics made with U.S.-sourced active ingredients and tested in U.S. labs. This isn’t just about efficiency-it’s about quality control. Studies done in the U.S. under FDA oversight are more reliable and easier to audit.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working on new guidance for 45 complex drug types by mid-2024. That includes better in vitro methods for topical products and standardized approaches for inhalers and transdermal patches. International alignment is growing too. The FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) now agree on 87% of bioequivalence standards. That means a generic approved in the U.S. is more likely to be accepted in Europe-and vice versa.For manufacturers, the message is clear: don’t guess. Study the PSGs. Follow the FDA’s latest guidance. Use validated methods. And never assume that because a drug looks similar, it behaves the same. Bioequivalence isn’t just paperwork-it’s science that keeps millions of patients safe.

What is the main goal of a bioequivalence study?

The main goal is to prove that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This ensures the generic will have the same therapeutic effect and safety profile.

Do all generic drugs need human clinical trials?

No. Some products, like eye drops, ear drops, and certain topical creams, can qualify for a biowaiver if they meet strict criteria for ingredient matching and physical properties. In those cases, in vitro testing is enough.

Why is the 80/125 rule used for bioequivalence?

The 80/125 rule is based on decades of clinical data showing that when drug exposure falls within this range, therapeutic outcomes are effectively identical. It balances safety with practicality-allowing for minor natural variations without risking patient health.

What are narrow therapeutic index drugs, and why are they treated differently?

Narrow therapeutic index (NTID) drugs, like warfarin or levothyroxine, have a very small difference between an effective dose and a toxic one. For these, the FDA tightens the bioequivalence range to 90-111% to minimize the risk of under- or over-dosing.

How long does it typically take to complete a bioequivalence study?

A standard bioequivalence study takes 6 to 12 months to plan, conduct, analyze, and submit. The actual clinical phase-where volunteers take the drugs and give blood samples-usually lasts 2 to 4 months. But delays often happen during data review or if the FDA requests additional information.

Can a generic drug be approved without testing in the U.S.?

Technically, yes-if the study meets FDA standards, it can be done overseas. But the FDA strongly prefers U.S.-based studies because they’re easier to inspect and verify. The Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program gives faster review to studies conducted in the U.S. with U.S.-sourced ingredients.

Andy Cortez

February 8, 2026 AT 03:17Joseph Charles Colin

February 9, 2026 AT 14:03Randy Harkins

February 9, 2026 AT 16:25Tori Thenazi

February 10, 2026 AT 06:46Frank Baumann

February 10, 2026 AT 08:25Alex Ogle

February 11, 2026 AT 03:00Brandon Osborne

February 12, 2026 AT 16:15Lyle Whyatt

February 13, 2026 AT 13:19Random Guy

February 14, 2026 AT 17:22Chelsea Cook

February 14, 2026 AT 21:03John Sonnenberg

February 15, 2026 AT 07:07Jessica Klaar

February 16, 2026 AT 15:46PAUL MCQUEEN

February 17, 2026 AT 03:27Chima Ifeanyi

February 18, 2026 AT 09:52