Heart Failure Diuretic & Potassium Management Tool

Current Potassium Assessment

Quick Reference Guide

Results & Recommendations

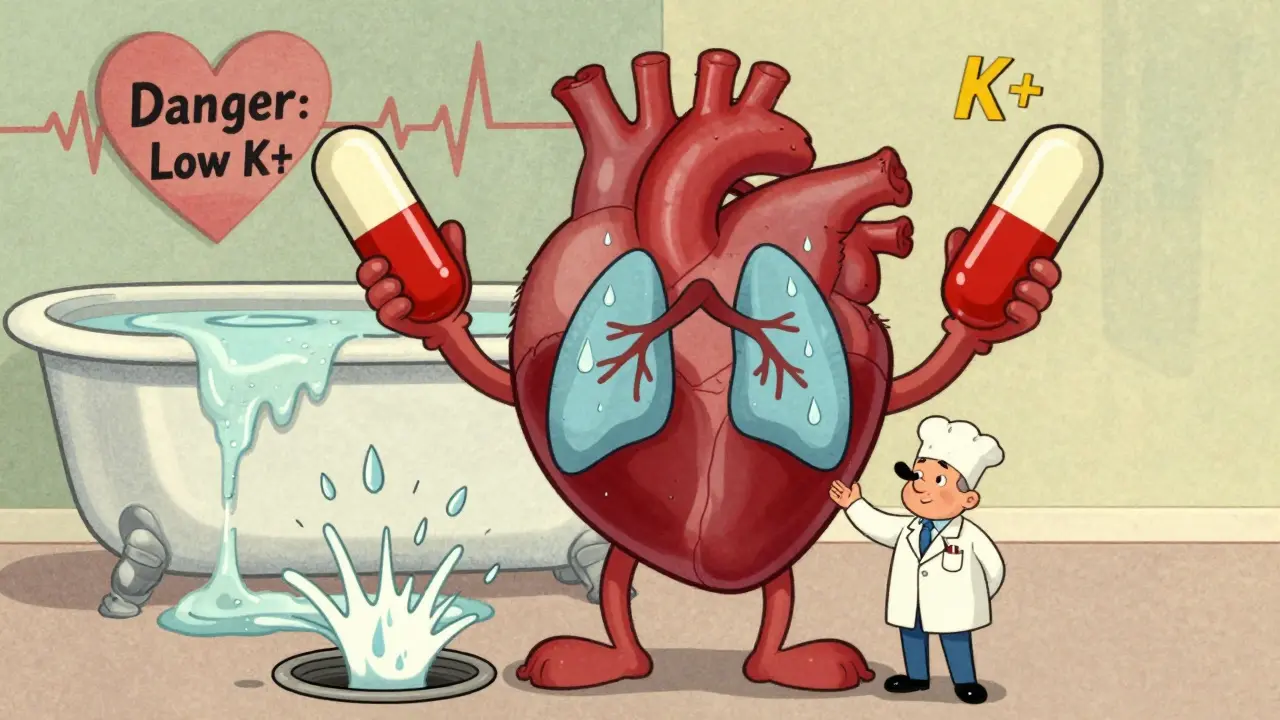

When you have heart failure, fluid buildup in your lungs and legs is one of the most frustrating parts of the disease. Diuretics-commonly called water pills-are the go-to treatment to flush out that excess fluid. But there’s a hidden cost: many patients end up with dangerously low potassium, a condition called hypokalemia. It’s not just a lab number you ignore. Low potassium can trigger irregular heartbeats, make heart failure worse, and even increase your risk of dying. The good news? You don’t have to accept it as inevitable. With the right approach, you can manage diuretics effectively while keeping your potassium where it needs to be: between 3.5 and 5.5 mmol/L.

Why Diuretics Cause Low Potassium

Loop diuretics like furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide are the most powerful tools doctors use to remove fluid in heart failure. They work by blocking salt reabsorption in the kidneys, which pulls water out with it. But here’s the catch: when salt leaves, potassium follows. The more diuretic you take, the more potassium your body loses through urine. This isn’t a side effect-it’s built into how these drugs work.Studies show that 20-30% of heart failure patients on loop diuretics develop hypokalemia. The risk goes up if you’re on high doses, take diuretics only once a day, or are also using other potassium-wasting meds like steroids or laxatives. Even worse, some patients don’t feel a thing until they have an arrhythmia. That’s why checking potassium isn’t optional-it’s lifesaving.

The Danger of Low Potassium

Potassium isn’t just for muscle cramps. It’s critical for your heart’s electrical system. When levels drop below 3.5 mmol/L, the risk of dangerous heart rhythms-like ventricular tachycardia or torsades de pointes-goes up by 1.5 to 2 times. In heart failure patients, whose hearts are already weakened, this isn’t theoretical. A 2020 study in Hypertension found that patients with potassium under 3.5 mmol/L had a significantly higher chance of dying within a year.And it’s not just about the number. The bigger issue is the pattern. Taking furosemide once a day causes big spikes in potassium loss, followed by periods of recovery. This rollercoaster makes your heart more vulnerable. Giving the same total dose split into two smaller doses-say, 20 mg in the morning and 20 mg at noon-smooths out the peaks and lowers the risk.

How to Fix It: Potassium Replacement

If your potassium dips below 3.5 mmol/L, you need to act. But not all replacements are the same.- For mild low potassium (3.0-3.5 mmol/L): Start with oral potassium chloride, 20-40 mmol per day. This is usually in tablet or liquid form. Take it with food to avoid stomach upset.

- For severe low potassium (under 3.0 mmol/L): You’ll likely need IV potassium in the hospital. Doses are given slowly-no more than 10-20 mmol per hour-while you’re on a heart monitor. Giving it too fast can stop your heart.

Don’t just reach for banana supplements. Potassium chloride is the standard because it’s the form your body uses most efficiently. Other forms like potassium citrate or gluconate are less effective for correcting acute losses.

Don’t Just Replace-Prevent

Replacing potassium is like bailing water from a leaky boat. The real fix is plugging the hole. That’s where potassium-sparing diuretics come in.Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) like spironolactone and eplerenone block the hormone aldosterone, which is responsible for pushing potassium out of the body. The RALES trial showed that spironolactone cut death risk by 30% in severe heart failure-not just because it helped with fluid, but because it kept potassium stable.

Start low: 12.5-25 mg of spironolactone daily, or 25 mg of eplerenone. Check potassium in 3-5 days. These drugs can cause potassium to rise too high, especially if you have kidney problems. But when used right, they’re one of the best ways to prevent hypokalemia without stopping diuretics.

The New Players: SGLT2 Inhibitors

In the last five years, a new class of drugs has changed how we treat heart failure: SGLT2 inhibitors. Originally for diabetes, drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin have proven powerful in heart failure-even if you don’t have diabetes.They work by making your kidneys dump sugar and salt in the urine. But unlike loop diuretics, they don’t cause big potassium losses. In fact, they’re neutral or slightly beneficial for potassium levels. Clinical trials show they reduce the need for diuretics by 20-30%. That means less potassium washed out, less risk of low levels, and fewer hospital visits.

The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines now recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for all heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction, and even many with preserved ejection fraction. They’re not a replacement for diuretics-but they’re a powerful partner. If you’re on high-dose furosemide and still struggling with fluid, ask your doctor if an SGLT2 inhibitor could help you lower your diuretic dose.

What About Diet?

You’ve probably heard to eat more potassium-rich foods: bananas, potatoes, spinach, beans, oranges. That’s true-but it’s not enough.Heart failure patients are often told to cut salt to less than 2-3 grams per day. That helps with fluid, but here’s the twist: low salt intake triggers your body to produce more aldosterone. And more aldosterone means more potassium lost in urine. So while salt restriction is important, it can accidentally make hypokalemia worse.

The answer isn’t to eat more salt. It’s to combine salt control with potassium-sparing meds and careful monitoring. Don’t rely on diet alone to fix low potassium. It’s a backup, not a solution.

Monitoring: When and How Often

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Here’s the real-world schedule that works:- When starting or changing a diuretic: Check potassium every 3-7 days for the first 2 weeks.

- Once stable: Monthly checks are fine for most people.

- During hospitalization for worsening heart failure: Check every 1-3 days. Things can change fast.

- If you add an MRA or SGLT2 inhibitor: Check potassium at day 3, then again at day 7.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Fatigue, muscle weakness, or palpitations can be subtle-or absent. Blood tests are your best friend.

What to Avoid

Some common practices make hypokalemia worse:- Using thiazide diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide or metolazone with loop diuretics without monitoring potassium. This combo is strong-but dangerous if potassium isn’t watched closely.

- Skipping doses of potassium supplements because you feel fine. Potassium levels can drop overnight.

- Using NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) regularly. These drugs reduce kidney blood flow and make diuretics less effective, leading to higher doses-and more potassium loss.

- Ignoring laxative use. Chronic laxative abuse is a hidden cause of low potassium in older adults.

What’s Next?

The future of diuretic management is personalized. Instead of giving everyone the same dose of furosemide, doctors are starting to use biomarkers like BNP (a heart stress marker) and eGFR (kidney function) to tailor doses. Early data suggests this cuts hypokalemia rates by 15-20%.Extended-release diuretics are also in development. These release the drug slowly over 12-24 hours, avoiding the big potassium swings caused by standard doses. They’re not widely available yet, but they’re coming.

And while potassium binders like patiromer are mainly used for high potassium, researchers are looking at whether they can help fine-tune levels in patients who swing between too high and too low. It’s early, but promising.

Bottom line: Diuretics save lives in heart failure. But they need to be used smartly. Low potassium isn’t just a side effect-it’s a warning sign. By combining the right meds, monitoring closely, and using newer tools like SGLT2 inhibitors, you can stay fluid-free without putting your heart at risk.

Can I just eat more bananas to fix low potassium from diuretics?

No. While bananas and other potassium-rich foods are healthy, they won’t correct a significant drop caused by diuretics. You need oral potassium chloride supplements or potassium-sparing medications like spironolactone. Food alone can’t raise levels fast or reliably enough in heart failure patients.

Is it safe to take potassium supplements with heart failure?

Yes, if done correctly. Oral potassium chloride is safe for most heart failure patients with mild to moderate low potassium. But if you have kidney disease or are on an MRA like spironolactone, your doctor must monitor your levels closely. Too much potassium can be just as dangerous as too little.

Why do I need to take my diuretic twice a day instead of once?

Taking a single large dose causes a big spike in fluid and potassium loss, followed by a rebound where your body holds onto salt again. Splitting the dose-like 20 mg in the morning and 20 mg at noon-gives more consistent diuresis and reduces potassium swings. It also lowers the risk of nighttime urination and keeps your levels steadier.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors replace diuretics?

Not completely, but they can reduce your need for them. SGLT2 inhibitors help your body get rid of fluid naturally and reduce heart strain without causing potassium loss. Many patients can lower their diuretic dose by 20-30% when adding one. They’re now a standard part of heart failure treatment, not just a backup.

How often should my potassium be checked if I’m on diuretics?

When you start or change your diuretic, check every 3-7 days for the first two weeks. Once stable, monthly checks are usually enough. But if you’re hospitalized for worsening heart failure, get checked every 1-3 days. Don’t wait for symptoms-low potassium often has none until it’s dangerous.

Corey Sawchuk

January 17, 2026 AT 08:37Nicholas Gabriel

January 18, 2026 AT 01:18Cheryl Griffith

January 18, 2026 AT 21:35Ryan Hutchison

January 19, 2026 AT 13:14Melodie Lesesne

January 21, 2026 AT 00:39brooke wright

January 21, 2026 AT 20:40Nick Cole

January 23, 2026 AT 05:07Riya Katyal

January 24, 2026 AT 17:22Henry Ip

January 24, 2026 AT 23:32swarnima singh

January 26, 2026 AT 20:10Isabella Reid

January 27, 2026 AT 21:44kanchan tiwari

January 28, 2026 AT 06:59Allen Davidson

January 29, 2026 AT 01:41