Antibiotic Liver Injury Calculator

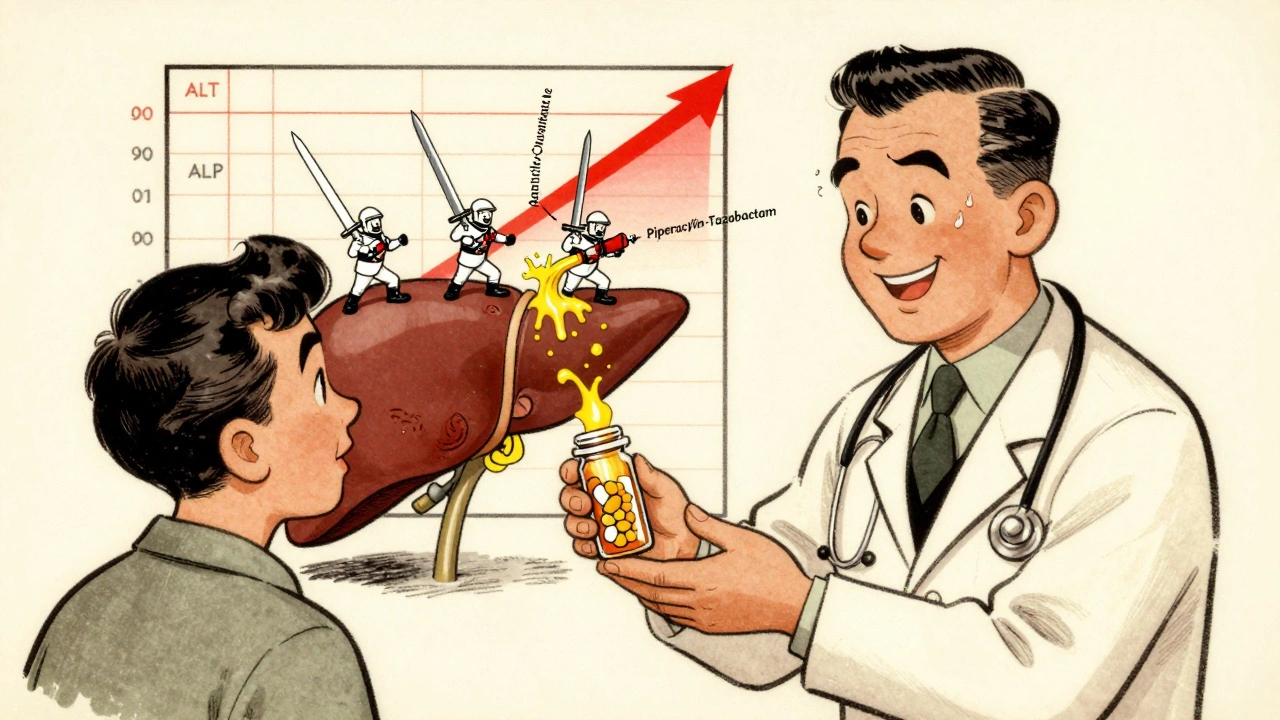

This calculator uses the R-ratio (ALT/ALP) method to determine if antibiotic-related liver injury shows patterns of hepatitis, cholestasis, or mixed injury based on your lab results.

Article reference: According to the article, R > 5 indicates hepatitis, R < 2 indicates cholestasis, and 2 ≤ R ≤ 5 indicates mixed injury.

Results

Antibiotics save lives, but they can also quietly damage the liver. For every 100,000 prescriptions of amoxicillin-clavulanate, 15 to 20 people will develop noticeable liver injury. That’s not rare-it’s common enough that doctors should be watching for it. Most people don’t know antibiotics can cause hepatitis or cholestasis until their blood tests show abnormal liver enzymes. By then, the damage may already be done. The problem isn’t just one drug. It’s a whole class of medications, used millions of times a year, with unpredictable effects on the liver.

How Antibiotics Hurt the Liver

Antibiotics don’t just kill bacteria-they disrupt the body’s balance in ways that can harm the liver. The two main patterns of injury are hepatitis and cholestasis. Hepatitis means the liver cells themselves are damaged. Cholestasis means bile isn’t flowing properly, so toxins build up. The difference shows up in blood tests. If ALT (alanine aminotransferase) is more than five times the upper limit of normal, it’s likely hepatitis. If ALP (alkaline phosphatase) is more than twice normal, it’s likely cholestasis.

Some antibiotics favor one pattern over the other. Amoxicillin-clavulanate causes cholestasis in 70 to 80% of cases. Fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin and azithromycin often cause mixed injury, where both ALT and ALP rise together. The reason? Different drugs trigger different molecular reactions. Some block mitochondria-the energy factories inside liver cells. Others create toxic byproducts that attack liver tissue. Some even change the gut microbiome so badly that harmful bacteria start leaking into the bloodstream, reaching the liver and causing inflammation.

The gut-liver connection is critical. Antibiotics wipe out good bacteria that keep the intestinal barrier strong. When that barrier breaks down, bacterial fragments enter the portal vein and head straight to the liver. Studies show people with low levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a key beneficial gut bacterium, have more than three times the risk of developing antibiotic-related liver injury. This isn’t just theory-it’s measurable, repeatable, and now part of ongoing clinical trials.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

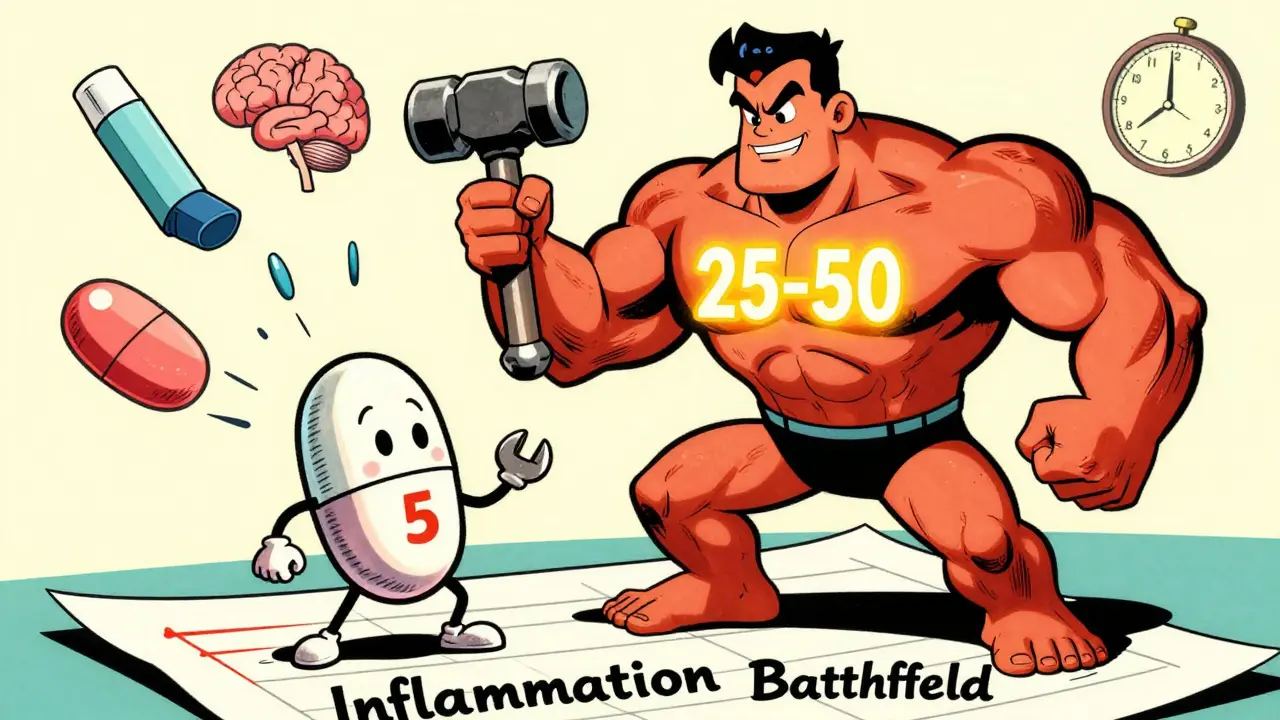

Not everyone who takes antibiotics gets liver injury. But some people are far more vulnerable. The biggest risk factor? Duration. Taking antibiotics for seven days or longer increases the chance of liver damage by 3.2 times compared to shorter courses. That’s not a small jump-it’s a major red flag.

ICU patients are especially at risk. One study found that 28.7% of patients on piperacillin-tazobactam for more than a week developed liver injury. That’s nearly one in three. Even more concerning: meropenem, often seen as safer, still caused injury in 12.3% of long-term users. And it’s not equal across genders-men are 2.4 times more likely than women to suffer liver damage from meropenem.

Sepsis is another hidden risk. Patients already fighting a severe infection have an 80% higher chance of developing antibiotic-related liver injury. Why? Their livers are already stressed. Adding antibiotics on top of inflammation, low blood pressure, and organ strain pushes them over the edge. The FDA’s adverse event database confirms this pattern: sepsis and antibiotic use together create a dangerous synergy.

Genetics matter too. Certain HLA gene variants make some people more likely to have an idiosyncratic reaction-meaning their immune system attacks the liver after exposure to a specific antibiotic. This isn’t dose-dependent. One pill might be fine. The next could trigger injury. That’s why some people get hurt after one course, while others take the same drug for months with no issues.

Which Antibiotics Are the Worst?

Not all antibiotics carry the same risk. The LiverTox database, maintained by the National Institutes of Health, rates drugs on a 10-point scale for hepatotoxicity. Amoxicillin-clavulanate scores 8 to 10-high risk. Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are moderate risk (5 to 7). Most others fall below 4.

Here’s what the data shows:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate: Highest population-attributable risk. Causes cholestasis in most cases. Onset: 1 to 6 weeks after starting.

- Piperacillin-tazobactam: 28.7% injury rate in ICU patients on long courses. Often requires stopping therapy.

- Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin): Mixed injury pattern. Onset: 1 to 2 weeks. Lower incidence but still dangerous in vulnerable patients.

- Rifampin: Dose-dependent toxicity. Rarely used alone, but dangerous when combined with isoniazid.

- Meropenem: Lower overall risk, but higher in men. Still a concern in critically ill patients.

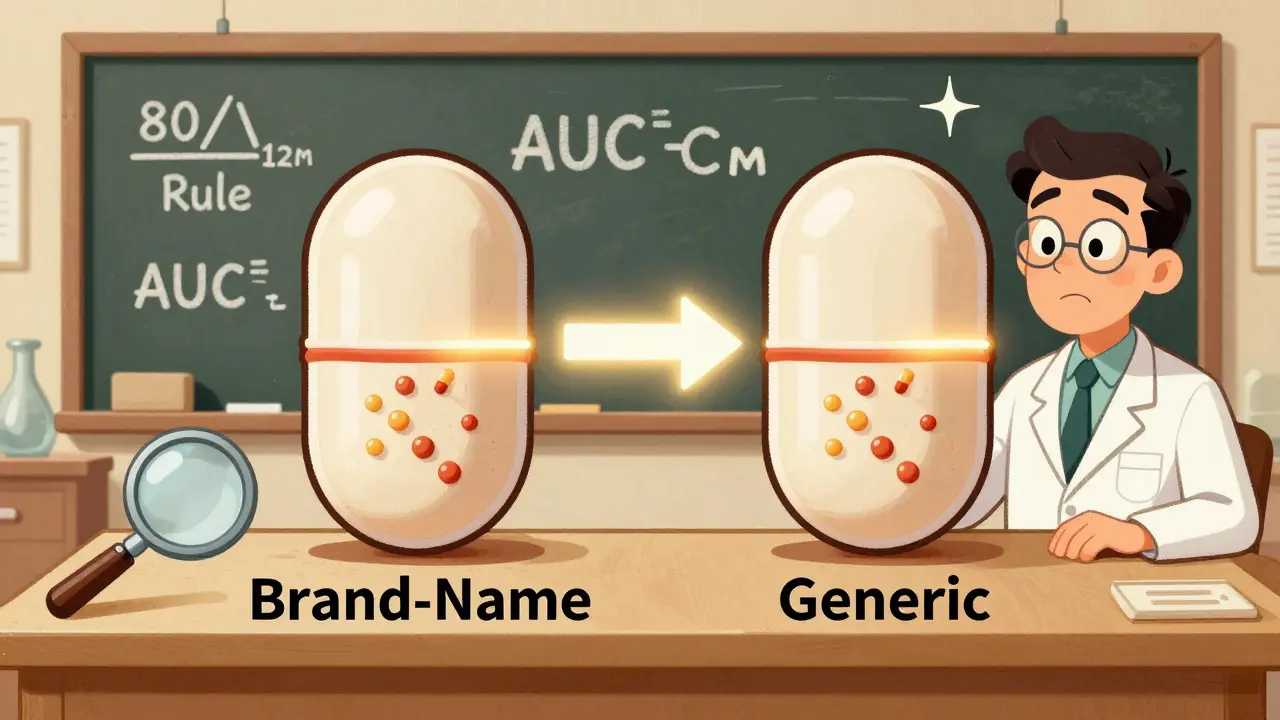

What’s surprising? Even common antibiotics like azithromycin-often considered safe-can cause mixed liver injury in 60% of documented cases. The assumption that “oral antibiotics are harmless” is outdated. The liver doesn’t care if the drug is taken at home or in the hospital. It only responds to exposure, dose, and individual biology.

How Doctors Spot the Problem

Diagnosing antibiotic-induced liver injury is like solving a puzzle with missing pieces. The first step is timing. Did the enzymes rise after starting the drug? Did they drop after stopping it? That’s the classic clue.

Doctors use the R-ratio to classify injury:

- R > 5 = hepatocellular (hepatitis)

- R < 2 = cholestatic

- 2 ≤ R ≤ 5 = mixed

But blood tests alone aren’t enough. In ICU patients, it’s hard to tell if elevated enzymes come from antibiotics, sepsis, low blood flow to the liver, or even a bile duct infection. That’s why many clinicians follow the “rule of 5”: stop the antibiotic if ALT is more than five times normal, or if ALP is more than twice normal and the patient has symptoms like jaundice, nausea, or fatigue.

Some hospitals monitor liver tests weekly for patients on long-term antibiotics. Others only check at baseline and then again after two weeks. There’s no universal standard. That inconsistency is part of the problem. A 2023 study found that 37.4% of patients on piperacillin-tazobactam had ALT over three times normal-but only 12.8% had the drug stopped. Many doctors wait too long.

What to Do If You’re on Antibiotics

If you’re prescribed an antibiotic, especially for more than five days, ask: Is this necessary? Is there a safer alternative? Should I get my liver checked? You don’t need to refuse treatment-but you do need to be informed.

For high-risk drugs like amoxicillin-clavulanate or piperacillin-tazobactam, baseline liver tests before starting are essential. Repeat testing after 7 to 10 days is a smart precaution. If you develop unexplained fatigue, dark urine, pale stools, or yellowing of the eyes or skin, get tested immediately. Don’t wait for your next appointment.

There’s no antidote for antibiotic-induced liver injury. The only proven treatment is stopping the drug. Most people recover fully within weeks to months. But in rare cases, it leads to acute liver failure. That’s why early detection saves lives.

What’s Next for Prevention

The future is personal. Researchers are now testing gut microbiome panels to predict who’s at risk before they even start antibiotics. If your stool sample shows low levels of beneficial bacteria, your doctor might choose a different antibiotic-or add a probiotic to protect your liver.

Clinical trials are underway to see if specific probiotics can reduce liver injury. Early results are promising. Other studies are looking at genetic testing for HLA markers that signal high risk. Within five to seven years, we may be able to say: “Based on your DNA, avoid amoxicillin-clavulanate.” That’s not science fiction-it’s already in phase 2 trials.

For now, the best defense is awareness. Antibiotics are powerful tools, but they’re not harmless. The liver doesn’t scream when it’s hurt-it whispers. And if you’re not listening, the damage can become irreversible.

Can antibiotics cause permanent liver damage?

In most cases, no. Once the antibiotic is stopped, the liver begins to heal, and enzyme levels return to normal within weeks or months. However, in rare cases-especially if the injury is severe and goes undetected-acute liver failure can occur, which may require a transplant. Permanent damage is uncommon but possible if treatment is delayed.

Are over-the-counter antibiotics linked to liver injury?

In the U.S., true antibiotics require a prescription. Some people confuse antibacterial supplements or topical products with oral antibiotics, but these don’t carry the same liver risks. However, in countries where antibiotics are sold without a prescription, misuse leads to higher rates of liver injury. Always take antibiotics exactly as prescribed.

How long after stopping an antibiotic does liver function improve?

ALT and ALP levels typically start dropping within days after stopping the drug. Most patients see normalization within 4 to 8 weeks. Severe cases may take 3 to 6 months. Regular follow-up blood tests are recommended until levels return to normal.

Can I take a different antibiotic if I had liver injury from one?

Yes, but only after careful evaluation. Not all antibiotics cause the same type of injury. If you had cholestasis from amoxicillin-clavulanate, you may still tolerate a fluoroquinolone or macrolide. But avoid the same class or structurally similar drugs. Always inform your doctor about past liver injury from antibiotics.

Do natural supplements help protect the liver from antibiotic damage?

There’s no strong evidence that milk thistle, NAC, or other supplements prevent antibiotic-related liver injury. Some may even interfere with drug metabolism. The only proven strategy is monitoring liver enzymes and stopping the drug early if signs appear. Probiotics are being studied, but they’re not yet standard care.

Final Thoughts

Antibiotic-related liver injury isn’t a footnote-it’s a silent epidemic. Millions of prescriptions are written every year, and many of them come with an unspoken risk. The good news? We know more than ever about who’s at risk, which drugs are dangerous, and how to catch it early. The bad news? Most people-including many doctors-still don’t look for it until it’s too late.

Knowledge is your best protection. Ask questions. Get tested. Track your symptoms. Your liver can’t tell you it’s hurting-but your blood test can. Don’t ignore the signs. The right antibiotic can save your life. The wrong one, taken without caution, could put it at risk.

Rebecca Braatz

December 5, 2025 AT 01:30Wow, this is exactly why I started pushing my docs to check liver enzymes before any long-term antibiotic course. I had a friend who almost lost her liver because no one thought to monitor. It’s not just about the drug-it’s about the person behind the prescription. We need standardized protocols, not guesswork.

zac grant

December 6, 2025 AT 10:13From a clinical pharmacology standpoint, the R-ratio is underutilized in primary care. Most GPs still just look at ALT and panic. The cholestasis vs hepatocellular distinction changes everything-dosing, monitoring, even prognosis. We’re missing a huge opportunity to personalize antibiotic stewardship.

Chase Brittingham

December 8, 2025 AT 03:14My brother took amoxicillin-clavulanate for a sinus infection and ended up in the ER with jaundice. They didn’t connect it until his ALT was 1200. No one warned him. No one asked about his meds. This needs to be standard patient education, not an afterthought.

Jake Deeds

December 8, 2025 AT 10:06It’s fascinating how we’ve turned antibiotics into candy. People pop them like aspirin. The gut-liver axis? Most patients don’t even know the liver has a gut. It’s not just medical ignorance-it’s cultural arrogance. We treat biology like a vending machine: insert pill, get cured. No wonder things break.

Bill Wolfe

December 8, 2025 AT 20:37Let’s be real-Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know this. They profit from antibiotics, they profit from liver transplants, they profit from follow-up care. The fact that amoxicillin-clavulanate is still first-line? Pure greed. And the FDA? Asleep at the wheel. Wake up, people. This isn’t science-it’s a corporate playbook.

Benjamin Sedler

December 9, 2025 AT 19:47So let me get this straight-you’re telling me that my grandma’s ‘natural’ turmeric supplement is riskier than the antibiotic she’s on? I mean, I get the science, but come on. If we’re going to scare people about meds, maybe stop selling ‘immune boosters’ that are just sugar and glitter.

Ollie Newland

December 10, 2025 AT 11:23Interesting that the UK’s NICE guidelines don’t mandate routine LFT monitoring for outpatient antibiotics. We’ve got data showing 1 in 5000 prescriptions leads to significant injury. That’s higher than some vaccine adverse events. Why aren’t we acting?

George Graham

December 10, 2025 AT 19:58I’ve seen this too many times. A patient comes in with fatigue, dark urine, and the doctor says, ‘Must be the flu.’ No labs. No questions. It breaks my heart. We’re so focused on treating the infection that we forget the body’s other systems. A simple ALT/ALP check takes two minutes. It’s not hard-it’s just not prioritized.

Michael Feldstein

December 12, 2025 AT 02:16Does anyone track how many people stop antibiotics early because they’re scared of liver damage? I wonder if we’re causing more harm by scaring people into non-compliance than we are by the injury itself. Balance is everything.

Joe Lam

December 13, 2025 AT 02:28Oh please. You’re all acting like this is some groundbreaking revelation. The LiverTox database has been public since 2008. Doctors who don’t know this are either lazy or incompetent. Stop pretending this is a mystery-it’s negligence dressed up as awareness.

michael booth

December 13, 2025 AT 03:14Augusta Barlow

December 14, 2025 AT 21:02Think about this: what if the real problem isn’t the antibiotics-but the glyphosate in our food, the EMFs from our phones, the fluoride in our water, and the 5G towers that weaken our liver’s detox pathways? The antibiotics are just the trigger. The real epidemic is environmental toxicity, and the medical system is too blind to see it. They want you to blame the pill, not the poison in your breakfast cereal.