Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) doesn’t respond to hormone therapy or HER2-targeted drugs. That leaves chemotherapy as the main tool-for now. But the landscape is changing fast. In 2025, doctors aren’t just guessing anymore. They’re using biomarkers, sequencing tumors, and even designing custom vaccines. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening in hospitals right now, and patients are seeing real differences in survival and side effects.

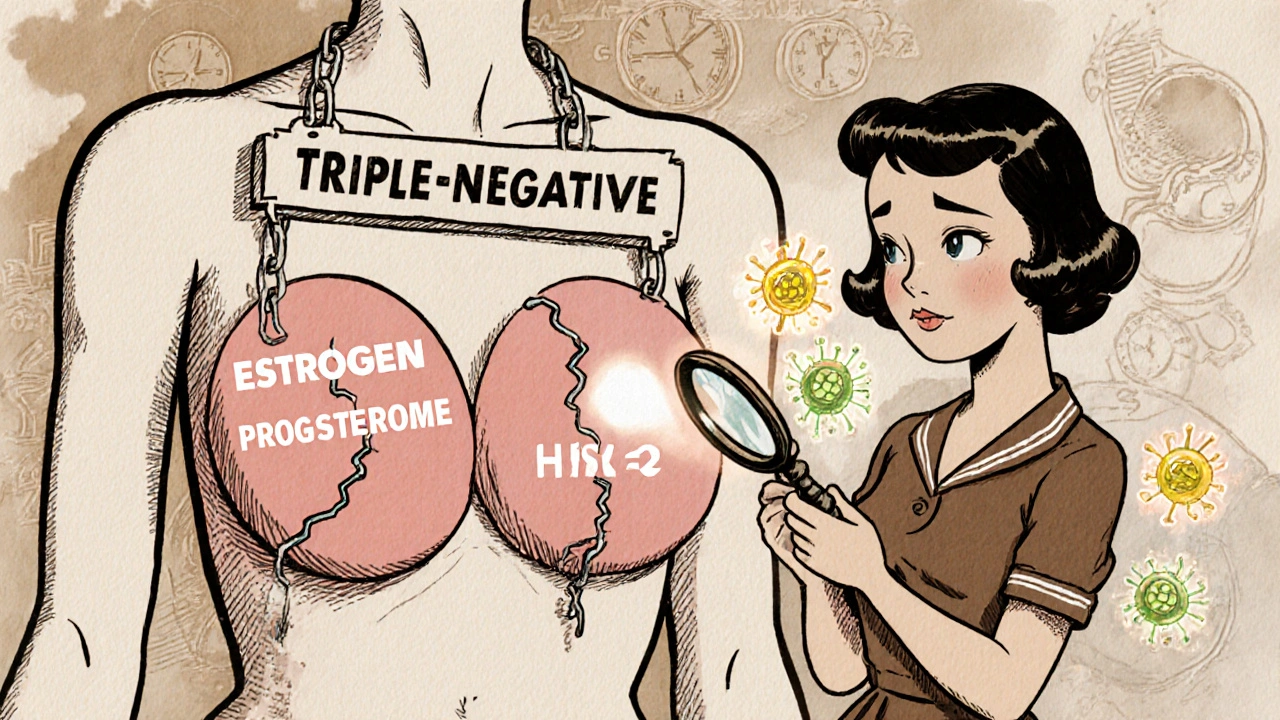

What Makes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Different?

Not all breast cancers are the same. Most have receptors for estrogen, progesterone, or HER2-proteins that drugs can latch onto to stop cancer growth. TNBC lacks all three. That’s why it’s called triple-negative. It’s aggressive, often diagnosed in younger women, and more likely to come back within the first three to five years after treatment. About 10% to 15% of all breast cancers are TNBC, but they account for a disproportionate number of deaths.

Without receptors to target, traditional hormone pills or drugs like trastuzumab don’t work. That’s why chemotherapy has been the go-to for decades. But chemo hits everything-healthy cells and cancer cells alike. The side effects are brutal: fatigue, nausea, hair loss, nerve damage, and long-term risks like heart problems. And even then, many tumors don’t shrink enough.

Now, researchers are looking at what makes each tumor unique. Some TNBCs have BRCA gene mutations. Others express PD-L1, a protein that helps cancer hide from the immune system. A few have high levels of certain proteins that can be targeted by new drugs. The key is testing early and often.

Standard Treatment Today: Chemo, Surgery, and Beyond

For early-stage TNBC, the standard still starts with neoadjuvant chemotherapy-meaning chemo before surgery. The goal? Shrink the tumor so surgeons can remove it more easily and check how well the cancer responded. A complete response-no cancer left in the breast or lymph nodes after chemo-is a strong sign the patient will do well long-term.

Common chemo regimens include drugs like doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel. But in recent years, platinum-based drugs like carboplatin have become part of the mix, especially for patients with BRCA mutations. Studies show platinum chemo improves pathologic complete response rates by 10% to 15% compared to standard chemo alone.

After chemo, surgery follows-either a lumpectomy or mastectomy. Then comes radiation for many patients, and sometimes more chemo afterward (adjuvant therapy). But here’s the twist: timing matters more than ever.

Immunotherapy: Turning the Body’s Defense Against Cancer

Immunotherapy doesn’t kill cancer directly. It removes the brakes on the immune system so it can find and destroy cancer cells. For TNBC, the key marker is PD-L1. If a tumor tests positive (CPS ≥10), adding immunotherapy to chemo can double the chance of a complete response.

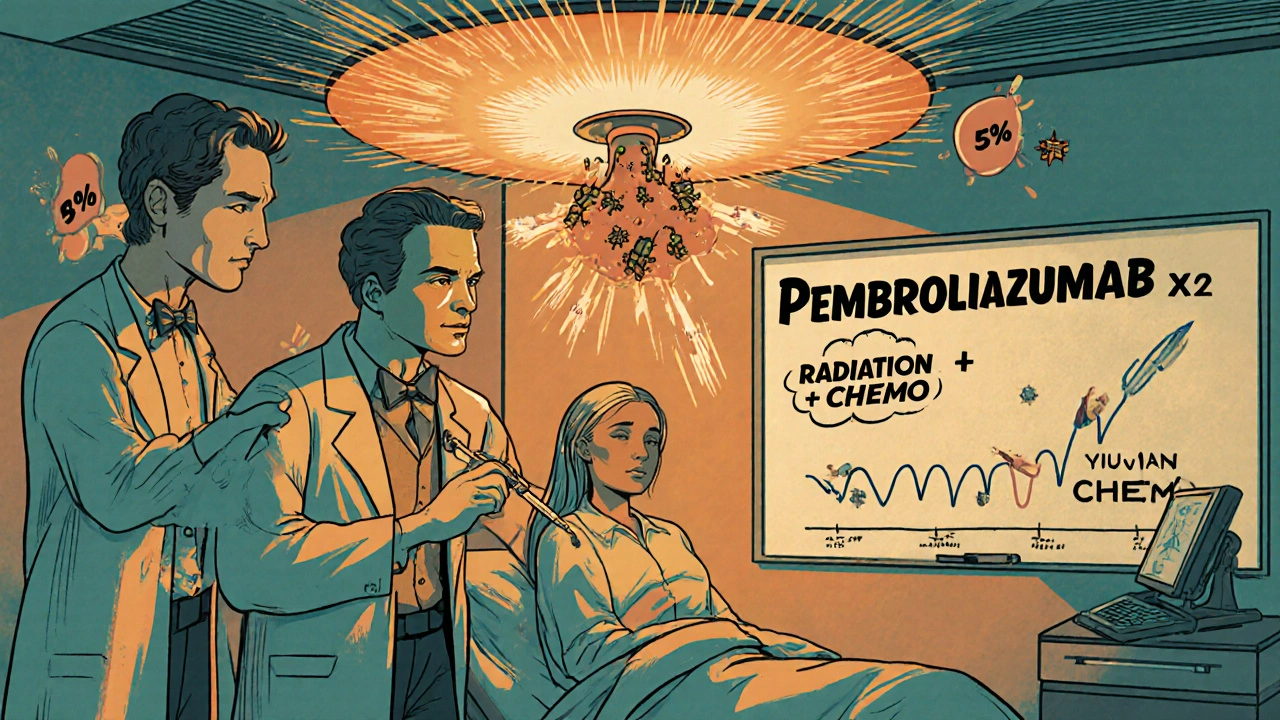

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is the most widely used immunotherapy for TNBC. The KEYNOTE-522 trial showed that when given before surgery with chemo, it boosted complete response rates from 51% to 64.8% in PD-L1-positive patients. That’s a big jump. It also improved survival over time.

But not everyone benefits. PD-L1-negative TNBC patients saw only a small improvement. That’s why testing is non-negotiable. The 22C3 pharmDx test is the standard used to decide who gets pembrolizumab.

And here’s something new: a 2025 study from UT Southwestern Medical Center flipped the script. Instead of giving multiple doses of pembrolizumab over months, they gave just two doses at the start-right after radiation. Then they moved straight to chemo. The result? A 59% complete response rate-just as good as KEYNOTE-522-but with only 41% serious side effects, compared to 82% in the original trial.

This isn’t just about less chemo. It’s about smarter sequencing. Radiation early may prime the immune system, making the immunotherapy more effective with fewer doses. This approach could become the new standard.

Targeted Drugs: PARP Inhibitors and Antibody-Drug Conjugates

For TNBC patients with inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (about 15% to 20%), PARP inhibitors like olaparib and talazoparib are game-changers. These drugs exploit a weakness in cancer cells with broken DNA repair systems. In the OlympiAD trial, patients on olaparib lived 7.8 months longer without their cancer worsening compared to those on standard chemo.

But what if you don’t have a BRCA mutation? That’s where antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) come in. These are like smart missiles: a monoclonal antibody finds the cancer cell, then delivers a powerful toxin directly inside.

Sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) targets the TROP-2 protein, which is found on most TNBC cells. In the ASCENT trial, it doubled the median progression-free survival compared to chemo in patients who’d already tried two prior treatments. The response rate was 35%, and some patients stayed in remission for over a year. The catch? Side effects are serious-61% had severe low white blood cell counts, and 37% had severe diarrhea.

Another ADC, trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), was originally made for HER2-positive cancer. But it’s now being used in TNBC with very low HER2 levels-something called HER2-low. In the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, it achieved a 37% response rate in these patients. That’s a new category of TNBC patients who can now benefit from a drug they’d have been excluded from just a few years ago.

The Future: Personalized Vaccines and Dual-Target Therapies

One of the most exciting developments is coming from Houston Methodist Hospital. They’ve built a lab that can sequence a patient’s tumor, identify its unique mutations, and make a custom vaccine in just six weeks. The vaccine teaches the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells carrying those exact mutations.

In phase I trials, 78% of patients showed a strong immune response after receiving the vaccine alongside pembrolizumab. The goal? Prevent recurrence after chemo and surgery. If this works, it could turn TNBC from a disease that comes back into one that’s controlled-or even cured.

Another frontier is dual-target therapy. Instead of one drug, combine two that hit different pathways at once. For example, blocking CDK12 and PARP together causes synthetic lethality-cancer cells die because they can’t repair DNA or control cell division. In lab models, this combo stopped 68% of tumor growth, compared to 32% with just one drug.

Other combinations being tested include CDK4/6 inhibitors with PI3K inhibitors, or EZH2 inhibitors with CDK9 blockers. These are still in early trials, but they show how researchers are moving beyond single-agent approaches to tackle the complexity of TNBC.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond?

The treatment landscape for TNBC has shifted dramatically since 2018. Five new therapies have been approved: pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, olaparib, talazoparib, and sacituzumab govitecan. More are on the way.

By 2028, experts predict over half of TNBC treatment decisions will be based on detailed biomarker profiles-not just PD-L1 and BRCA, but also HRD status, tumor mutational burden, and gene expression patterns. Hospitals will need teams of oncologists, genetic counselors, pathologists, and data scientists working together to interpret results.

And access remains a problem. In low- and middle-income countries, only 35% to 40% of patients get tested for biomarkers. Without testing, they can’t get the best treatments. This isn’t just a medical issue-it’s an equity issue.

The five-year survival rate for metastatic TNBC is still only 12% to 15%. That’s far below other breast cancer subtypes. But the momentum is there. Clinical trials are growing: over 1,500 are active worldwide, making TNBC the most researched breast cancer subtype today.

What Should Patients Do Now?

If you’ve been diagnosed with TNBC, here’s what matters:

- Get biomarker testing done at diagnosis: PD-L1, BRCA1/2, and ideally HRD status.

- Ask if you’re eligible for neoadjuvant therapy with immunotherapy and platinum chemo.

- Find out if your hospital offers clinical trials-especially for ADCs, vaccines, or dual-target combinations.

- Discuss sequencing: Could radiation come earlier? Could immunotherapy be reduced?

- Work with a multidisciplinary team. TNBC is too complex for one doctor to manage alone.

There’s no magic bullet yet. But the path forward is clearer than ever. Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all anymore. It’s tailored, precise, and increasingly personalized. And for the first time, many patients with TNBC are seeing real hope-not just survival, but quality survival.

Is triple-negative breast cancer curable?

Early-stage triple-negative breast cancer can be cured in many cases, especially if the tumor responds well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy. A complete pathologic response-no cancer left after treatment-is a strong predictor of long-term survival. But TNBC has a higher risk of recurrence than other types, especially within the first 3 to 5 years. For metastatic TNBC, a cure is not yet possible, but new treatments are helping people live longer with better quality of life.

What is the best treatment for triple-negative breast cancer in 2025?

There’s no single "best" treatment-it depends on your tumor’s biology. For early-stage TNBC with PD-L1 positive status, the standard is pembrolizumab plus platinum-based chemo before surgery. For those with BRCA mutations, adding a PARP inhibitor after chemo improves outcomes. For metastatic disease, sacituzumab govitecan or trastuzumab deruxtecan (if HER2-low) are top options after prior chemo. The UT Southwestern protocol (radiation + two pembrolizumab doses + chemo) is emerging as a less toxic alternative with similar results.

Do all TNBC patients need chemotherapy?

Most do, especially in early stages, because there are no approved hormone or HER2-targeted options. But the amount and type are changing. Some patients now get less chemo when combined with immunotherapy or radiation. In advanced cases, if a patient has a targetable mutation like BRCA or a high TROP-2 expression, targeted drugs like PARP inhibitors or ADCs may be used instead of or after chemo. Chemo is still central, but it’s no longer the only tool.

What are the side effects of new TNBC treatments?

Immunotherapy can cause fatigue, rash, and autoimmune reactions like thyroid or colon inflammation. PARP inhibitors often cause anemia, nausea, and fatigue. Sacituzumab govitecan leads to severe neutropenia in over half of patients and frequent diarrhea. Trastuzumab deruxtecan carries a rare but serious risk of lung inflammation. The new UT Southwestern protocol reduces these risks by cutting back on immunotherapy doses and timing radiation earlier. Side effects are still a challenge, but newer strategies aim to balance effectiveness with safety.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for a TNBC clinical trial?

If you’ve been diagnosed with TNBC, ask your oncologist about trials at your center or nearby academic hospitals. Trials are open to patients at all stages-from newly diagnosed to those who’ve had multiple treatments. You’ll need recent tumor tissue for biomarker testing (PD-L1, BRCA, HRD, etc.). Many trials now require specific molecular profiles. If you’re eligible, trials may offer access to drugs not yet widely available, like personalized vaccines or dual-target therapies. Don’t wait until standard options run out-consider trials early.

Are there any new drugs coming for TNBC in 2026?

Yes. Datopotamab deruxtecan, a new TROP-2 ADC from Roche, is in phase III trials and could be approved by late 2026. Adagloxad simolenin, a vaccine-like therapy targeting the MUC1 protein, is also in late-stage testing. Other promising candidates include drugs targeting LIV-1, FRα, and CDK12/PARP combinations. The NCCN guidelines are expected to update in May 2026 to include the UT Southwestern protocol and possibly new ADCs. The field is moving faster than ever.

What’s Next for TNBC Research?

The next five years will focus on turning TNBC from a deadly disease into a manageable one. Researchers are working on ways to make immunotherapy work for PD-L1-negative patients. They’re testing combinations of ADCs with immunotherapy. They’re exploring how the tumor microenvironment influences treatment response.

One major goal: reduce the burden of treatment. Less chemo. Fewer infusions. Fewer side effects. That’s what the UT Southwestern team proved is possible. And with personalized vaccines, the dream is no longer just surviving TNBC-but staying cancer-free without lifelong treatment.

For patients, the message is clear: know your tumor. Ask for testing. Ask about trials. And don’t accept the old rules. The old rules didn’t work well enough. The new ones are here-and they’re changing lives.

Brendan Peterson

November 16, 2025 AT 11:57Just read the UT Southwestern protocol again. Two doses of pembrolizumab after radiation? That’s wild. I’ve seen oncologists still pushing 18 cycles of immunotherapy like it’s a subscription service. Cutting it down and timing it with radiation? That’s not just smart-it’s elegant. The side effect drop from 82% to 41% is insane. Why isn’t this everywhere yet?

Jessica M

November 17, 2025 AT 01:14It is imperative to underscore that biomarker testing remains the cornerstone of personalized therapeutic intervention in triple-negative breast cancer. Without comprehensive genomic profiling, including PD-L1 status, BRCA1/2 mutations, and homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), patients are at risk of receiving suboptimal, non-targeted regimens. The ethical imperative to ensure equitable access to these diagnostics cannot be overstated.

Laura-Jade Vaughan

November 18, 2025 AT 23:16Okay but like… 🤯 the vaccine thing?? They’re making a custom vaccine in 6 weeks?? That’s faster than my Amazon delivery. I’m crying. Not because I have TNBC (I don’t) but because this is the future we’ve been waiting for. 💀💉 #ScienceIsMagic

Jennifer Stephenson

November 20, 2025 AT 14:40Chemo still sucks. But now it’s not the only option.

Segun Kareem

November 21, 2025 AT 03:52In Africa, we don’t even get the old chemo on time. How can we talk about vaccines and ADCs when a biopsy takes months? This isn’t innovation-it’s privilege. The real breakthrough isn’t in the lab. It’s in making sure the next person who hears 'triple-negative' isn’t told to go home and pray.

Philip Rindom

November 22, 2025 AT 06:55So… we’re saying chemo’s still the backbone, but now we’re just sprinkling fairy dust on it in the form of $500k drugs? I mean, congrats? But also… can we fix the cost? Or is this just a new kind of cancer lottery?

Jess Redfearn

November 22, 2025 AT 12:13Wait, so if I have TNBC, do I need to be rich to get the new treatments? Or is this just for people who live near big hospitals? My cousin got diagnosed last year and they didn’t even mention biomarkers. She just got chemo and a sad look.

Ashley B

November 23, 2025 AT 07:34They’re hiding something. Why are they pushing all these expensive drugs so fast? Big Pharma knows the survival rates are still 12%. They’re not curing anyone-they’re just making people pay to die slower. And don’t get me started on those ‘personalized vaccines’-they’re just using your DNA to sell you more chemo. I read a blog post that said the FDA is in their pocket.

Scott Walker

November 23, 2025 AT 18:46Man, I just lost my mom to this. Saw her go through chemo, then the new combo, then… nothing. But that vaccine thing? That gave me chills. If it works even half as good as they say… I’d drive across the country for it. 🤍

Sharon Campbell

November 25, 2025 AT 01:45ok but like… why is everyone acting like this is new? chemo’s been the only thing for 20 years and now suddenly we have ‘targeted therapies’? i think they just renamed chemo and added a fancy word. also who even has time to get all these tests? my aunt just got a text saying ‘call us in 2 weeks’ and that was it.

sara styles

November 26, 2025 AT 15:50You think this is progress? Let me tell you what’s really happening. The FDA approved all these drugs because they were bribed by pharma lobbyists. The real cure is vitamin D and turmeric, but they don’t patent that. The BRCA testing? It’s a scam to sell more drugs. And the ‘personalized vaccine’? That’s just a fancy way of saying they’re injecting your tumor cells back in and calling it science. The government doesn’t want you cured-they want you on lifelong treatment. Look up Operation ChemoGate. It’s all documented.

Erika Lukacs

November 26, 2025 AT 16:31One cannot help but reflect on the existential implications of this medical paradigm shift. We are no longer treating disease-we are engineering identity through molecular profiling. The self becomes a dataset. Is this healing… or is this the commodification of biology?

Rebekah Kryger

November 27, 2025 AT 12:19ADCs are the future? More like the placebo effect with a side of neutropenia. TROP-2 expression? That’s just a fancy biomarker they made up to sell another $120k drug. And don’t get me started on ‘HER2-low’-that’s not a subtype, that’s a marketing ploy. If it’s not HER2-positive, it’s not HER2 anything. Stop redefining biology to fit your trial endpoints.

Victoria Short

November 28, 2025 AT 18:33so like… is this all just for people who can afford to fly to Houston for a vaccine? because my local hospital doesn’t even have a genetic counselor.

Eric Gregorich

November 30, 2025 AT 11:05I’ve been following this for years. I’m not a doctor, but I’ve read every paper, every trial, every patient forum. And let me tell you-this is the most exciting thing I’ve seen in my lifetime. The UT Southwestern protocol? That’s the future. The vaccine? That’s the holy grail. But what nobody’s talking about is the emotional toll. You’re not just fighting cancer-you’re fighting a system that doesn’t care if you live or die unless you’re profitable. And that’s the real triple-negative: the disease, the cost, and the silence. We need to scream louder. Not just for survival. For dignity.