High elevations: stay safe, feel better faster

Above about 8,000 feet (2,400 m) your body starts to feel the thinner air. If you're going to mountains, ski resorts, or high plateaus, know the common problems, how to prevent them, and when to get help. This page gives clear, practical tips on symptoms, simple first-aid, and the most used medicines—without the medical jargon.

Short ascents are usually fine, but rapid climbs raise the risk of acute mountain sickness (AMS). AMS often begins with headache, nausea, dizziness, trouble sleeping, and fatigue. Most mild cases improve with rest, slower ascent, and hydration. If you get severe breathlessness, confusion, inability to walk straight, or vomiting that won’t stop, treat this as an emergency—descend and seek medical care right away.

Practical steps before and during ascent

Plan your itinerary so you gain elevation slowly—no more than 1,000 feet (300 m) a day above 8,000 feet if possible. Spend an extra day to acclimatize every few thousand feet. Stay well hydrated and eat small meals. Avoid heavy exercise the first day at a new altitude and limit alcohol and sedatives, which can make breathing problems worse. Sleep lower than your highest daytime climb when possible—"climb high, sleep low" helps your body adjust.

Medications and tools that help

Some medicines can prevent or treat altitude illness. Acetazolamide (Diamox) is commonly used to help with acclimatization; people usually start it a day before ascent and continue for a few days, but discuss dosing with a clinician. For headaches and fever, acetaminophen or ibuprofen are useful. Dexamethasone is a steroid used for severe cases or as a temporary bridge to descent—only under medical advice. Anti-nausea medicines can ease vomiting so you can hydrate. Portable oxygen and portable hyperbaric bags are helpful for emergency treatment during remote trips.

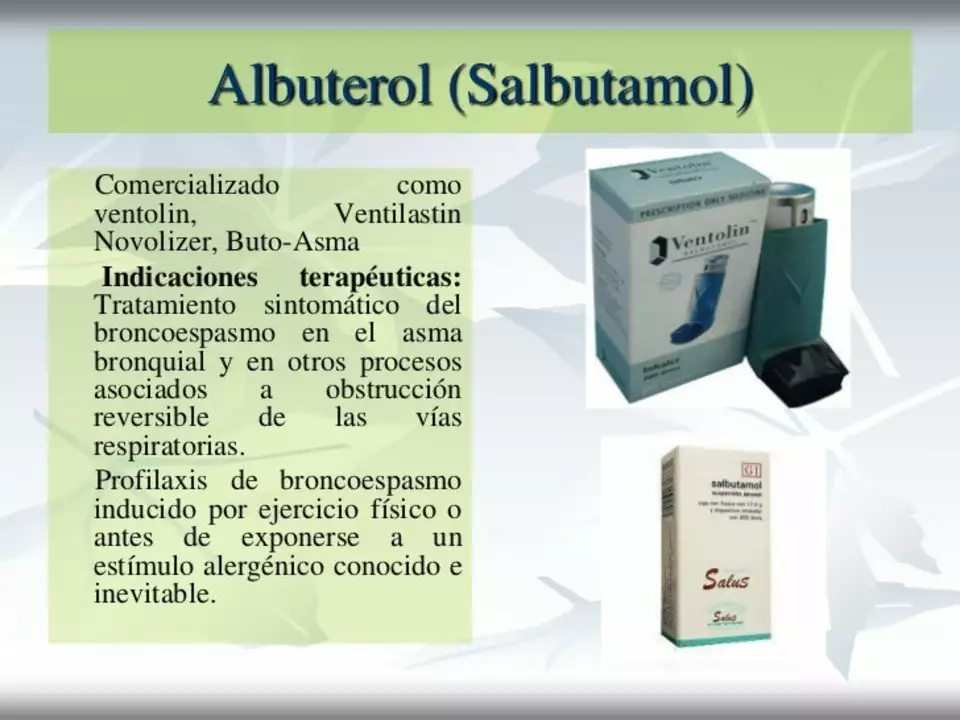

People who have heart or lung disease, pregnancy, or recent illness should talk with their doctor before traveling to high elevations. Some chronic conditions make altitude travel risky or require extra planning. If you use regular prescription inhalers, bring extra and pack them in carry-on luggage.

Bring a small pulse oximeter if you can—it's cheap and tells you quickly if oxygen saturation falls. Kids and older adults often show symptoms differently: watch for fussiness, poor eating, or confusion. Consider travel insurance that covers evacuation when you'll be remote. If in doubt, descend a few hundred meters and reassess—descent is the most effective treatment and safer than waiting for symptoms to get worse every time.

Watch your travel companions. AMS can progress quickly—check for changes in mood, coordination, and breathing. If someone improves after rest and slowing the climb, continue cautiously. If symptoms worsen or include confusion, severe breathlessness, or coughing up pink frothy sputum, descend immediately and call emergency services.

Simple preparation makes a big difference: plan gradual gains, pack basic meds, know emergency descent routes, and ask your healthcare provider about prevention if you’re at higher risk. High places can be beautiful—just respect the altitude so you can enjoy them safely.

Albuterol and Altitude: Managing Asthma at High Elevations

- 20 Comments

- Apr, 27 2023

As someone with asthma, I understand the challenges faced when traveling to high elevations. Albuterol plays a crucial role in managing asthma symptoms at these heights. The thin air and low oxygen levels can make breathing difficult, but using an albuterol inhaler helps to relax the airways, making it easier to breathe. It's essential to consult with a doctor before venturing to high altitudes, and always carry an inhaler as a precaution. Proper preparation ensures that we can safely enjoy our adventures without worrying about asthma complications.