Diuretic Drug Interaction Checker

Check if your diuretic combination could cause dangerous electrolyte imbalances. Based on clinical evidence from the article.

Diuretics are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the world, especially for managing high blood pressure, heart failure, and fluid buildup. But behind their effectiveness lies a hidden risk: electrolyte changes and drug interactions that can turn a routine treatment into a medical emergency. If you’re taking a diuretic-or care for someone who is-you need to know what’s really happening inside the body, not just what the pill bottle says.

How Diuretics Work (And Why They Mess With Your Electrolytes)

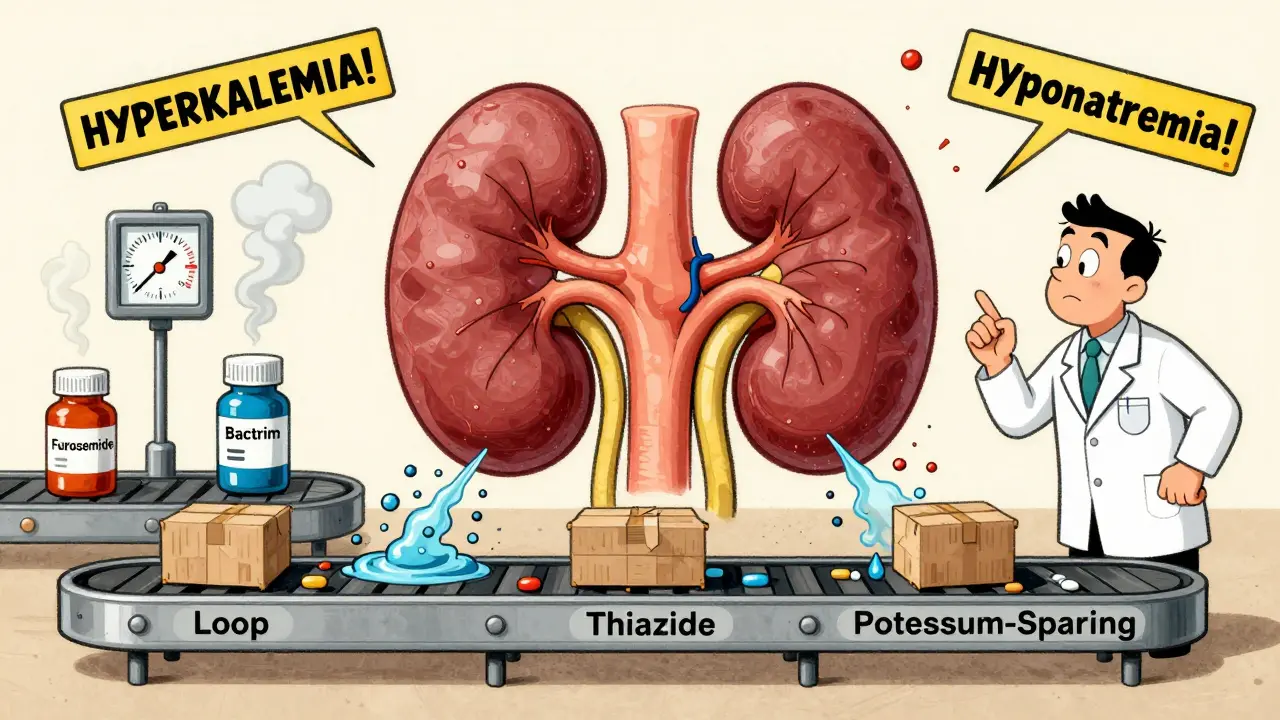

Diuretics don’t just make you pee more. They change how your kidneys handle sodium, water, and other minerals. There are three main types, each targeting a different part of the kidney:- Loop diuretics (like furosemide and bumetanide) block sodium reabsorption in the loop of Henle. This is the strongest class, pushing out 20-25% of filtered sodium. That’s why they’re used in severe heart failure or kidney disease.

- Thiazide diuretics (like hydrochlorothiazide) work lower down, in the distal tubule. They’re milder, removing only 5-7% of sodium, which makes them better for long-term blood pressure control.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics (like spironolactone and amiloride) don’t cause potassium loss-but they can push potassium too high. They work by blocking aldosterone or sodium channels in the collecting duct.

Here’s the catch: every time your kidneys flush out sodium, they pull water with it. But they don’t do it evenly. Loop diuretics cause you to lose more water than salt, which can spike sodium levels in your blood (hypernatremia). Thiazides, on the other hand, impair your kidney’s ability to dilute urine, leading to low sodium (hyponatremia)-especially in older women. Potassium-sparing diuretics prevent potassium loss, but that’s a double-edged sword: they can cause dangerous high potassium (hyperkalemia), particularly if you have kidney problems.

A 2013 study of 20,000 ER patients found that people on loop diuretics were more than twice as likely to have low potassium, while those on thiazides had over three times the risk of low sodium. Potassium-sparing drugs nearly quadrupled the risk of high potassium. And here’s the scary part: all of these imbalances increased the chance of dying in the hospital.

Drug Interactions: When Medicines Fight Each Other

Diuretics don’t live in isolation. They interact with other drugs in ways that can be deadly-or lifesaving.NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or naproxen) are a major problem. They reduce blood flow to the kidneys, which makes diuretics less effective. In some cases, NSAIDs can cut a loop diuretic’s power by half. If you’re on furosemide and take Advil for your arthritis, you might think the diuretic isn’t working-but it’s the painkiller that’s sabotaging it.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs (used for blood pressure and heart failure) seem helpful with thiazides. They reduce potassium loss and boost diuretic effect. But when you add a potassium-sparing diuretic like spironolactone to an ACE inhibitor, potassium can skyrocket. One study showed a 1.2 mmol/L jump in potassium levels-enough to cause heart rhythm problems or cardiac arrest.

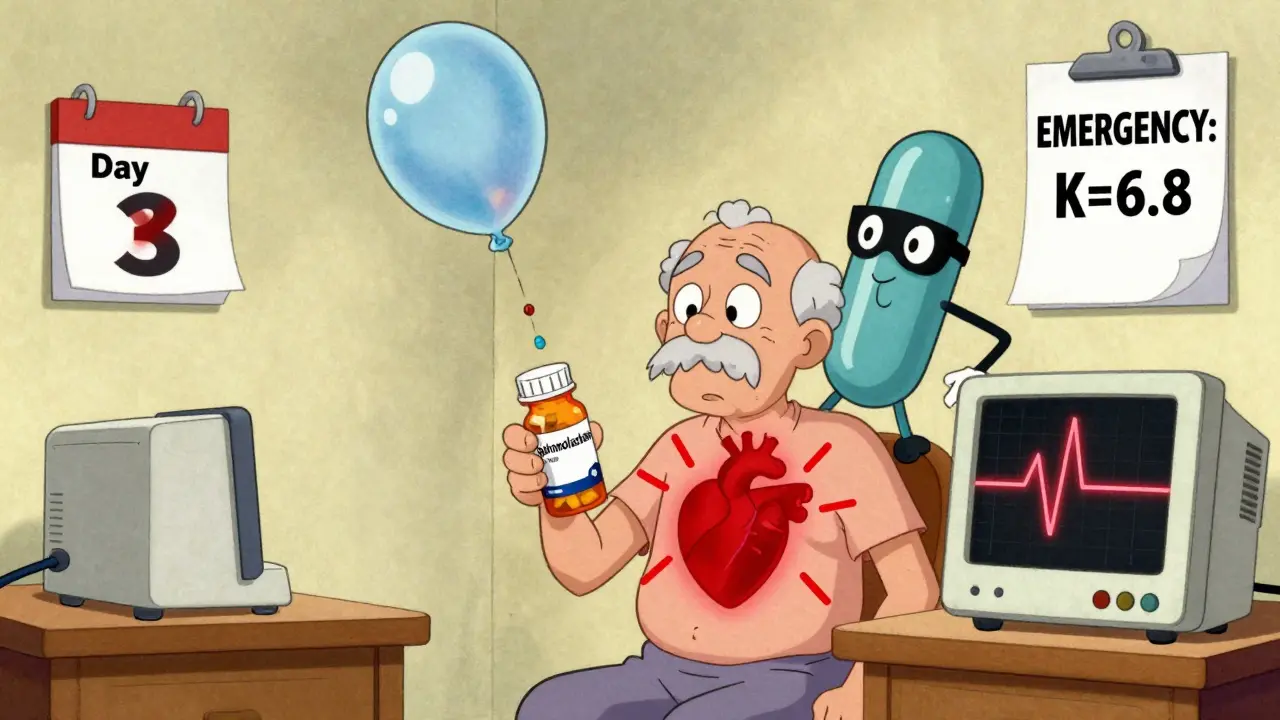

Even antibiotics can be dangerous. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) blocks potassium excretion in the kidneys. For someone on spironolactone, taking Bactrim for a UTI can push potassium from normal to life-threatening levels in just a few days. There are real cases on medical forums where patients ended up in ICU after this combination.

But not all interactions are bad. Newer diabetes drugs called SGLT2 inhibitors (like dapagliflozin) actually work better with diuretics. They reduce sodium reabsorption higher up in the kidney, which makes loop diuretics more effective. In fact, studies show the combination can reduce the diuretic dose needed by nearly a third. That’s why the American Heart Association now recommends adding dapagliflozin to diuretics for heart failure patients.

Diuretic Resistance: Why They Stop Working

If you’ve been on a diuretic for a while and suddenly stop losing fluid, you’re not imagining it. This is called diuretic resistance-and it’s common.When you take a loop diuretic, your kidneys respond by turning up sodium reabsorption downstream. Within 72 hours, the distal tubule starts working overtime to grab back the sodium you’re trying to flush out. That’s why doubling the dose often doesn’t help. The body adapts.

The solution? Combine diuretics that hit different parts of the kidney. Doctors call this “sequential nephron blockade.” For example, giving furosemide (loop) with metolazone (thiazide) can overcome resistance. The DOSE trial showed this combo worked in 68% of patients who didn’t respond to loop diuretics alone.

But this combo is risky. A 2017 study found 22% of patients on high-dose furosemide plus metolazone developed acute kidney injury. Another 15% had dangerously low sodium. That’s why this approach is reserved for severe cases and requires close monitoring.

What You Need to Monitor (And When)

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Electrolyte checks aren’t optional-they’re essential.- Check potassium and sodium within 3-7 days after starting a diuretic.

- For stable patients on long-term therapy, check every 1-3 months.

- If you’re on multiple diuretics or starting a new drug, check every 24-48 hours until levels stabilize.

For older adults, start low. A 12.5 mg dose of hydrochlorothiazide is safer than 25 mg. For people with kidney disease, furosemide dosing should be adjusted by body weight: 1 mg/kg if kidney function is moderate, 1.5 mg/kg if it’s poor.

Watch for symptoms: muscle cramps, weakness, irregular heartbeat, confusion, or swelling that won’t go down. These aren’t just side effects-they’re warning signs.

Real Cases, Real Risks

A 72-year-old man with heart failure was on 50 mg of spironolactone daily. He got a UTI and was prescribed Bactrim. Three days later, his potassium hit 6.8 mmol/L-dangerously high. He went into cardiac arrest. He survived, but only because his family recognized the symptoms and rushed him in. Another patient with cirrhosis and ascites had tried furosemide for months with no results. His doctor added amiloride and gave him a 25g IV albumin infusion. Within 10 days, he lost 8.2 kg of fluid-without his potassium dropping. That’s precision medicine. At Johns Hopkins, nurses implemented a simple protocol: automatic electrolyte testing within 72 hours of diuretic initiation. Over 18 months, hyponatremia cases dropped by 37%, hyperkalemia by 29%. Systems save lives.

The Future: Smarter Diuretics

In January 2024, the FDA approved Diurex-Combo-a single pill with furosemide and spironolactone. The DIURETIC-HF trial showed it cut heart failure readmissions by 22% and cut electrolyte emergencies in half. This isn’t just convenience-it’s safety by design. Meanwhile, AI-driven dosing tools are being tested. Mayo Clinic’s pilot program used machine learning to predict which patients would develop low potassium or high sodium based on age, kidney function, and other meds. It reduced emergencies by 40% in early trials. The next big shift? Moving away from one-size-fits-all dosing. Doctors are now looking at biomarkers: high urinary aldosterone? Add spironolactone. High chloride excretion? Try a thiazide. We’re entering an era of personalized diuretic therapy.What You Should Do Now

If you’re on a diuretic:- Ask your doctor: “Which type am I on, and why?”

- Know your last potassium and sodium levels. Keep a note in your phone.

- Never start a new medication (even OTC) without checking for interactions.

- Don’t ignore muscle cramps or fatigue-they might be electrolyte-related.

- Get blood tests done on time. Don’t wait until you feel bad.

Diuretics are powerful, but they’re not magic. They work because they change how your body handles salt and water. That same mechanism can also break your balance. The key isn’t avoiding them-it’s understanding them.

Can diuretics cause kidney damage?

Yes, but usually only if misused. Diuretics themselves don’t destroy kidneys, but they can cause acute kidney injury if they lead to severe dehydration or if combined with NSAIDs or other nephrotoxic drugs. This is most common with high-dose loop and thiazide combinations. Monitoring fluid intake and electrolytes prevents this.

Why do I feel weak on my diuretic?

Weakness is often a sign of low potassium (hypokalemia) or low sodium (hyponatremia). Loop and thiazide diuretics are the most likely culprits. A simple blood test can confirm this. Don’t assume it’s just aging or fatigue-get it checked.

Is it safe to take a diuretic with high blood pressure?

Yes-thiazide diuretics are actually first-line for high blood pressure. But they must be used carefully, especially in older adults. Starting with a low dose (12.5 mg hydrochlorothiazide) and monitoring sodium and potassium levels reduces risk. They’re safe when used properly.

Can I drink alcohol while on diuretics?

It’s not recommended. Alcohol increases fluid loss and can worsen low sodium or low potassium. It also raises blood pressure in the long term, which defeats the purpose of the diuretic. If you drink, limit it and monitor for dizziness or confusion.

Do I need to take potassium supplements with my diuretic?

Only if your doctor says so. Taking extra potassium without testing can be dangerous, especially if you’re on a potassium-sparing diuretic or an ACE inhibitor. Blood tests determine need-not symptoms. Never self-prescribe potassium.

What’s the safest diuretic for elderly patients?

For hypertension, low-dose thiazides (12.5 mg hydrochlorothiazide) are safest. For fluid overload, loop diuretics like furosemide are preferred, but dosing must be adjusted for kidney function. Avoid high doses and combinations unless absolutely necessary. Regular blood tests are non-negotiable.

Dusty Weeks

January 2, 2026 AT 22:18Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 4, 2026 AT 03:50Paul Ong

January 4, 2026 AT 20:59Bryan Anderson

January 5, 2026 AT 08:47Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 6, 2026 AT 15:27Richard Thomas

January 8, 2026 AT 11:45Austin Mac-Anabraba

January 8, 2026 AT 23:32Phoebe McKenzie

January 10, 2026 AT 18:12Kristen Russell

January 12, 2026 AT 09:15Andy Heinlein

January 12, 2026 AT 15:38Todd Nickel

January 13, 2026 AT 18:33Liam George

January 14, 2026 AT 08:48Ann Romine

January 16, 2026 AT 08:23Bill Medley

January 18, 2026 AT 03:21sharad vyas

January 19, 2026 AT 10:44